|

Up

Up

1903 Propellers

1903 Propellers

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

etting

out to make their first set of propellers in December 1903, the

Wright brothers were astounded to find there was no scientific basis

for propeller design. They had presumed that during the decades the

US. Navy had been using propellers, they would have developed some

mathematical theory for describing their performance. But the brothers

could find none -- the Navy's design method was simply "cut and try." etting

out to make their first set of propellers in December 1903, the

Wright brothers were astounded to find there was no scientific basis

for propeller design. They had presumed that during the decades the

US. Navy had been using propellers, they would have developed some

mathematical theory for describing their performance. But the brothers

could find none -- the Navy's design method was simply "cut and try."

Unwilling to leave this important process to chance, in January 1903 the Wrights built a

wind tunnel slightly larger than their 1901 tunnel and studied the

performance of 28-inch long propeller designs, developing their own

theory. Wilbur took the lead in this work as he had in their earlier

wind tunnel investigations. Possibly the most important discovery

that he made during these experiments was that a propeller was a wing traveling in a spiral

course. As such, it developed lift in a horizontal direction. This force,

combined with the reaction to the displacement of the air, was

thrust.

By February 1903 the brothers felt they had a firm grasp of

how a propeller worked. Wilbur designed and carved his first

full-size set of propellers -- 102 inches (2.6 meters) long,

tapering from 6 inches at the tip to two inches at the hub (15.2 cm

to 5 cm). Wilbur had determined he and Orv would need 90 pounds of

thrust to sustain the Flyer in flight at 24 mph (38.6 kph). When

tested at 245 rpm, the props fell short of the mark. Wilbur

determined that the reason was that the propeller pitch (the angle

at which the blade met the air) was too steep. In March, he began

designing an improved prop and by June 1903 he had carved two of

them -- one to turn clockwise on the right side of the Flyer and the

other to turn counterclockwise on the left. These counter-rotating

props would cancel the effects of any propeller torque that might

have otherwise pulled the Flyer to the left or right as it flew.

The new props were made from three laminated (glued face-to-face)

spruce boards. They were the same length at the first test prop, but

wider at the tip -- 8 inches (20.3 cm). Will had also adjusted the

pitch. The brothers had no opportunity to test the props at this

time -- they were consumed by other problems. But they were

confident of their work. When the brothers finally did get a chance

to test these propellers on the fully assembled Flyer at Kitty Hawk,

they found they produced a combined thrust of between 120 and 130

pounds at 330 rpm. They were also remarkably efficient, converting

66 percent of the mechanical energy from the motor into thrust.

References:

- Lippincott, Harvey H. Propulsion System of the Wright Brothers. In Wolko, Howard

S. (editor), The Wright Flyer, an Engineering Perspective. The Smithsonian Institution

Press, 1987, pp 79-82.

- McFarland, Marvin W. (ed) The papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright. McGraw-Hill Book

Co., New York, 1953, pp 1210-1214.

[Submitted by Joe W. McDaniel]

|

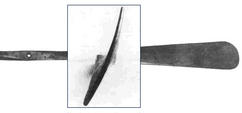

In early 1903, before designing their airplane propellers, the

Wrights first conducted wind tunnel experiments to determine how

propellers worked. These are some of the notes from their tests.

A side view of the 1903 propellers mounted on the Flyer in Kitty

Hawk. These were carved by hand from

laminated layers of spruce. The thin tips were covered with canvas to keep them from

splitting.

The propellers on the 1903 Wright Flyer in the Smithsonian Air &

Space Museum.

|

One of the most important conclusions the Wrights drew from their

experiments is that propellers are wings that revolve in circles and

produce lift. This propeller lift, however, is horizontal and

becomes thrust.

Like wings, propeller blades should be curved or cambered -- the

camber increases the amount of thrust produced.

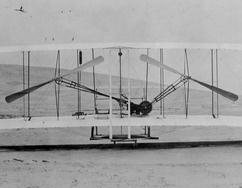

A rear view of the same props. Note that the chain drive on the left

is crossed -- the left propeller revolves counterclockwise while the

right revolves clockwise. The sideways torque generated by each prop

cancels out the other. Two props spinning in the same direction

would have given the Flyer a tendency to turn.

The props on the restored Flyer at the Smithsonian are not the

originals. These were damaged when the wind overturned the Flyer

after the fourth flight on 17 December 1903. The Smithsonian

displays one of the damaged original propellers separately from the

Flyer.

|