|

fter

the triumph of the first powered flights in 1903, 1904 was a trial. Even

before they began work, the brothers faced a tough decision. Flying, for them, had

grown to become more than an avocation.

They could not afford to devote the resources needed to continue their aeronautical experiments

without some sort of payback – their financial future was at stake.

Their bicycle business, which was already suffering from a

market-wide decline, had been shamefully neglected during 1902 and

1903 as they raced to get a powered airplane into the air. Could an

airplane business replace it? fter

the triumph of the first powered flights in 1903, 1904 was a trial. Even

before they began work, the brothers faced a tough decision. Flying, for them, had

grown to become more than an avocation.

They could not afford to devote the resources needed to continue their aeronautical experiments

without some sort of payback – their financial future was at stake.

Their bicycle business, which was already suffering from a

market-wide decline, had been shamefully neglected during 1902 and

1903 as they raced to get a powered airplane into the air. Could an

airplane business replace it?

On the long railroad journey back to Ohio from North Carolina, they

estimated what they had invested so far in research and development. All their aeronautical

experiments, including the materials needed to build their three

gliders and one Flyer, the four trips to and from Kitty Hawk, the

tents and sheds, even the wind tunnel had cost them a little

less than one thousand dollars That sounds absurdly inexpensive to

our twenty-first century ears, but it was the rough equivalent of

$60,000 to $70,000 US in today's currency – the research hadn't been

cheap. And still they didn't have a

marketable product. The Flyer had flown, but it was hardly a

practical flying machine. How much more time and money would it take

to develop their invention into a reliable form of transportation

that others would buy?

There was no clear answer. But, for the first time, they felt they

were at least within sight of a practical, salable airplane. They

had to try. So they let the bicycle business coast and concentrated

their efforts on developing their Flyer into a marketable product.

"We were compelled to regard it as a strict business

proposition," Wilbur later explained.

To take financial advantage of their work, they

would need a patent. They had already tried to file one themselves, but their application

had been rejected in 1903. So they decided to hire a professional patent attorney, Henry A. Toulmin, in nearby Springfield, Ohio. Toulmin advised them to continue work on a practical

flying machine, but to say as little as possible about their invention until the patent

was granted. In the meantime, he filed for a patent not just in the United

States, but many European countries as well.

To make real progress, the Wrights decided to bring their test flights closer to home.

During Orville's last years in school, the one subject he had loved above all others was

botany. It was taught by William Werthner, a noted scientist who had

pioneered the teaching of science in American high schools. Werthner loved

to get his students hands-on with science. He led his classes on field trips to

Huffman Prairie (between Dayton and

Springfield) to study the unique prairie environment. This was where, in the 1830s, botanist John Leonard Riddell had discovered three new

species of plants. Wilbur and Orville took another expedition out to the Prairie

to see if it might serve as a flying field.

At first glance, it seemed an unlikely choice. The Prairie was smaller than

the Wrights could have wished. It had poor drainage, making it wet and

marshy much of the year. And it was not flat. The area was covered

with small mounds, probably owing to the "hummock sedge" that

commonly grew in Ohio fens and bogs. In a letter, Wilbur described

making his way across the Prairie "jumping from hummock to hummock."

However, on closer inspection, Huffman Prairie had one important

characteristic that recommended it over many other Dayton-area

fields and pastures. The peat-like soil was soft and springy, not at

all like the unyielding clay typical of Ohio farms. The moisture in

the peat froze during the winter, making the soil expand – a

phenomenon known as a

"frost heave." This created tiny air pockets when the water melted in the

spring. The Wrights must have reasoned that the soft, heaved soil

could provide a measure of protection in the event of a hard landing

or a crash, as did the soft sands of Kitty Hawk.

Additionally, the Prairie was on the Interurban, the electric trolley line that

served the Dayton area – the Wrights could travel from West Third

Street to Simms Station, just across the road from Huffman Prairie,

in less than an hour. They asked permission from Torrence Huffman,

who owned an 84-acre tract of Huffman Prairie, to use it for their experiments. Huffman was bemused at their request,

but he saw no harm in letting them use this unproductive piece of land. His

only request was that they not harm the cows or horses that were

pastured there. (Privately, he

told Dave Beard, who lived on a farm next to Huffman Prairie, that he thought the Wright

brothers were "fools.")

The Wrights built a hangar in a corner of the Prairie, similar to their

hangar at Kitty Hawk and as remote as possible from the trolley stop.

They also built another airplane, the "Flyer II."

The 1904 Flyer II had a slightly flatter wing than the Flyer I, and its wing

ribs were much stronger and much simpler to construct. The skids were more

robust and held the propellers farther above the ground.. The Wrights also moved the pivot point of

the elevator so it wasn't so sensitive. But other than than, it was a clone

of the first Flyer. It even had a similar engine. Charlie

Taylor made two more horizontal four-cylinder engines with slightly larger

cylinders pistons and other improvements. One of these was used

for flying, replacing the engine that had been destroyed when a

gust of wind overturned the Flyer I. The second was a "bench engine." The

Wrights used it as a source of power for their experiments, especially their

experiments with propellers. They would also use it to test new ideas that

would help their engines develop more power or run cooler. If these ideas

worked, they transferred the improvements to their flying engine.

By May of 1904, the brothers were ready to resume

flying. They were beleaguered by another problem, however. Wild stories about their Kitty Hawk

flights circulated in the newspapers. (These had begun with a fantastic fabrication in the

Virginia-Pilot the day after the first flights -- "Flying Machine Soars 3

Miles in Teeth of High Wind...") The Wrights were genuinely amazed at the ease with

which the press manipulated the truth and were determined to correct the misconceptions

that abounded. They had issued a correction to the Associated Press on 5

January 1904, but the stories persisted – and grew in their audacity. In

February, without input or permission from either brother, The Independent magazine published a fictional account of

the first flights and signed Wilbur's name to it – The Experiments of a

Flying Man by Wilbur Wright. Hoping to set the record straight,

the brothers invited reporters from the prominent newspapers in Dayton and

Cincinnati to watch them fly their new machine with the understanding that there

would be no photographs allowed.

A crowd of about forty people gathered at Huffman Prairie on 23 May to watch

the Wright brothers fly. Although the Flyer I had

flown successfully just five months before, the Flyer II was reluctant to leave the

ground. The new engine was hard to start and continually misfired when the

brothers finally got it

going. Orville made a run down a 100-foot launching rail but never rose an inch off the

ground. They gathered the reporters again on 25 May, but a persistent rain

prevented them from attempting a launch. A very few reporters came out for a

third time on 26 May, but Orville managed only a brief hop of 25 feet.

Everyone went home disappointed – the reporters, the Wright brothers, even Bishop

Milton Wright wrote of the general discouragement in his diary. The Wrights hadn't shown

the world they could fly but, quite by accident, they had achieved one of their

objectives. The stories in the newspapers stopped. Based on what the

reporters had been

shown, they unanimously decided there was nothing to report. This was a bit

of good luck if only because it allowed the Wrights to work in relative

obscurity, undisturbed. Wilbur wrote to Octave Chanute, "The fact that we

are experimenting at Dayton is now public, but so far we have not been

disturbed by visitors. The newspapers are friendly and not disposed to

arouse prying curiosity in the community."

It was, perhaps, the only good luck they were to have for several months.

The remainder of the summer was a disappointing series of aborted launches

and crash-landings, often resulting in something breaking. Skids, spars,

rudder, elevator, and propellers snapped regularly. When the Flyer II

did fly, the flights were short and erratic with the Flyer "bobbing up and

down" or "undulating" throughout the brief time it was in the air. The

aircraft was unexpectedly unstable in pitch, with the nose always hunting up

or down. The Wright brothers mistakenly diagnosed the problem, deciding that

the Flyer II was balanced with its weight too far forward. They moved the engine and

radiator backwards, shortening the propeller shafts and supports to make the

airplane heavier in the tail. Resuming flight tests, the Wrights quickly

found that this only exacerbated the instability and they had to move

everything back. They even strapped iron weights to the skids just under the

elevator, moving the balance point forward from where it had been in May.

Still the Flyer undulated up and down. Wilbur wrote to Chanute, comparing

his and Orville's tribulations to those of the biblical prophet whom God had

jinxed: "We certainly have been "Jonahed" this year." Jonah aside, this

was the most difficult, the most crucial, and the most dangerous

juncture in the Wright brothers' quest to build a practical flying

machine. Will and Orv had returned from Kitty Hawk with less than

two minutes of experience between them piloting a powered airplane.

The Flyer II was unstable and unpredictable. Flying it would

have been a daunting task for an experienced test pilot, yet the

Wrights were learning to fly in this barely flyable aircraft.

That they did so is a testament to their ability to think through a

difficult problem, to manage enormous risk when testing a possible

solution, and to quickly learn the physical skills needed to operate

an ever-evolving machine. Because science advances through failure

as much as it does though success, the Wrights made progress in

spite of their alleged jinx. Little by little, their flights grew

longer; the crashes less severe. While the Flyer II remained

a cantankerous machine, their skill in handling it steadily

improved. On 13 August 1904, with their twenty-eighth test flight,

Wilbur managed to keep the airplane in the air for 1,304 feet (397

meters), surpassing for the first time his 852-foot flight on 17

December 1903 eight months previous. It was a short-lived victory,

however. On the same day, during the thirtieth flight of the season, Wilbur

crashed the Flyer II, breaking the elevator and a good deal

more. They crashed again three days later on 16 August. Eight days

after that, on 24 August, they up-ended the Flyer in a nose-first crash

leaving Orville "sore all over." In those eleven days, they had made

eleven flight attempts and only once had they exceeded that elusive

852-foot mark ― on August 22, their thirty-third flight had spanned

1,432 feet (436 meters). Most flights were under 200 feet (61

meters). Clearly sharpening their take-off skills would only carry them

so far. To make real progress, something more was needed.

|

Harry S. Toumlin, Sr. (seated) of Springfield, Ohio wrote and

filed the

Wright patent.

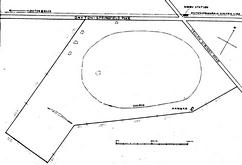

A map of the Huffman Prairie Flying Field at the junction

of Dayton-Springfield Pike and Yellow Springs Road. This was sketched by

Orville years after the flying experiments of 1904 and 1905.

Huffman Prairie was covered with small mounds or hummocks. This was

probably due to "hummock sedge," a type or prairie grass of found in

Ohio fens and bogs.

Today,

Huffman Prairie is part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. To visit

the Prairie in Google Earth,

CLICK

HERE.

Just a few years prior to 1904, the Dayton, Springfield and Urbana

Electric Railway had built a spur line that stopped at Simms Station,

just opposite Huffman Prairie.

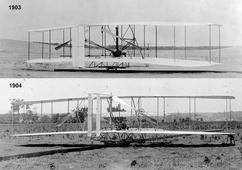

Wilbur and Orville talk in front of the Flyer II. Part of the wing is

still inserted in the shed they built to serve as a hangar. The Flyer

sat lengthwise in its hangar; Orville and Wilbur had to remove the front

elevator and the rear rudder to put the Flyer away.

The Wright Flyer II poised on its launching rail with the hangar/shed

behind it.

The 1904 Flyer II (bottom) was a virtual clone of the

1903 Flyer I (top). Because the Wrights made only four flights in their first aircraft before a gust of wind rolled it

over, they felt they had not adequately tested the design. So except for

some minor changes, the first two Wright Flyers were

identical.

Wilbur and Orville lay track -- the track had to be laid parallel to the

wind before each flight. Hoping to achieve the necessary speed for a successful

take-off, the Wrights often laid over 250 feet (76 meters) of track.

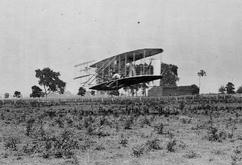

Initially, the Wrights could not get off the ground at Huffman Prairie,

but by mid-summer they were making short flights just a few feet off the

ground. This was their 19th

attempt to fly on 5 August 1904.

The Wrights didn't equal or surpass the distance they had flown at Kitty

Hawk in 1903 until 13 August 1904. This is a flight that Orville made

that day immediately after Wilbur flew 1,304 feet (397 meters).

Many of the early flights at Huffman Prairie ended

like this one on 24 August 1904, with the Flyer II crashed just a few hundred feet from the end

of the track. Note the "ski-jump" at the end of the rail to help get the

Flyer airborne. |