|

Up

Up

Aviation's Attic

Aviation's Attic

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

istory

is an endless storehouse of treasures, and pioneer aviation is one of its

richest rooms. Small wonder that pilots like to spend hours "hangar

flying," sharing tale after tale . Any aviation story worth telling

is rich with adventure and discovery. After all, these are tales about men

and women who fly, a unique and awesome ability that mankind

has only developed in the last century. istory

is an endless storehouse of treasures, and pioneer aviation is one of its

richest rooms. Small wonder that pilots like to spend hours "hangar

flying," sharing tale after tale . Any aviation story worth telling

is rich with adventure and discovery. After all, these are tales about men

and women who fly, a unique and awesome ability that mankind

has only developed in the last century.

Part of our job at the Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company is to dig up

pioneer aviation stories, brush them off, and share them with you. In

doing so, we organize that information so that it presents a coherent

picture of the lives of the Wright brothers and the history of early

aviation. But we occasionally find unique and interesting treasures that

don't quite fit the categories we've developed. Rather than ignore

these odd gems, we've decided to bring them front and center. Here, then

are a few of the unique and precious oddities that we've discovered in the

far corners of aviation's attic.

|

|

|

|

Griffith Brewer learned to fly at the Wright

Flying School. He was an English balloonist and

patent attorney who knew Wilbur and Orville throughout

their entire aviation career. He met Wilbur in France in

1908, the two became fast friends, and Wilbur treated

him to an airplane ride, making him the first Briton

ever to fly in a powered airplane. A few months later,

he met Orville when the younger brother joined Wilbur in

France, and Brewer hit it off with the other Wright as

well. Later, Brewer organized the British Wright

Company, representing the Wright's interests in England.

He also traveled to Ohio -- thirty times in all -- to

visits the Wrights in Dayton. In this short piece, he describes his first visit to

Dayton, Ohio, sharing interesting details and insights

about the Wright factory, their flight school, and

life at the Wright home.

|

Griffith Brewer at Simms Station.

|

|

|

For nearly thirty years, Orville Wright and the

Smithsonian Institution were at loggerheads over who

invented the airplane. In 1914, Glenn Curtiss in

partnership with the Smithsonian, dusted off the 1903

Langley Aerodrome, updated it, and made a few

hop-flights. The Aerodrome was a manned aircraft

designed by the late Smithsonian secretary, Samuel P.

Langley, who tried and failed to fly it in 1903,

just before the Wright bothers made their first

successful flights. The Smithsonian, after Curtiss flew

a much-modified Aerodrome, claimed that the original

aircraft could have flown before the Wright Flyer and

that the Langley Aerodrome was in fact the first

aircraft "capable of flight." This set off a controversy

that nearly lost America one of its dearest national

treasures.

|

The modified 1903 Langley Aerodrome in flight near Hammondsport, NY,

17 September 1914.

|

|

|

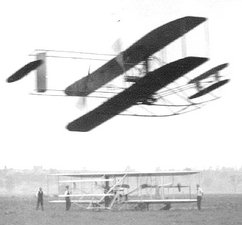

Thanks to several generous souls, we have uncovered 14 vintage photos

of the Wrights and their first pupils flying at Huffman Prairie and in

Sedalia, Missouri. The photos document the period when the Wright

brothers had begun to question the stability and efficacy of their

distinctive "tail-first" or canard design. They show how Wright

pilots experimented with and

compared with front elevators, back elevators, and elevators in

both the front and back. They also capture the moment just before he

Wrights adopted the conventional aircraft configuration with the main

wings forward and the elevator and rudder in back, forming an empennage

or "tail." |

Flying the Wright Model AB.

|

|

|

In this article Fred Kelly, the Wright brothers' only "authorized"

biographer, examines the popular myth that the Wrights were secretive,

hiding their early aeronautical experiments from the eyes of the public.

Kelly makes a convincing argument that they were not. Instead, he

presents evidence that this was an excuse that American journalists

adopted to cover their embarrassment for having completely overlooked

the biggest story of the twentieth century. The truth of the matter was

that the American media – in fact, the world media – just couldn't

bring themselves to believe that men had flown.

|

The Virginian Pilot breaks

the news of the Wright's first flights.

|

|

|

In 1909, several aviation enthusiasts in England had Thomas

W. K. Clarke build an updated version of the 1902 Wright Glider that they

could use for training while waiting for their powered aircraft to

be built. With Orville Wright's input, Clarke came up with a cross between the 1902 glider and a

Wright Model A. This was possibly the first "flight trainer" ever

made. In 1910, Clark deigned and built three additional

biplane gliders, including one that he advertised as an update of the

1896 Chanute-Herring glider, one of the gliders that had inspired

the Wright brothers. You could buy a Clark glider as a kit for £10.50 or

fully assembled for £34.00. |

Flying a Wright glider in England.

|

|

The first woman journalist to become famous for her interviews

takes on Wilbur and Orville -- and shows a completely different side of

the brothers other than the sober persona they projected to the world.

Kate Carew (her real name was Mary Williams) had a playful interview

style that she used to put her subjects at ease. The Wright brothers

apparently anticipated the fun and went at her with some playful jibes

of their own. |

Carew also drew these caricatures of the brothers.

|

|

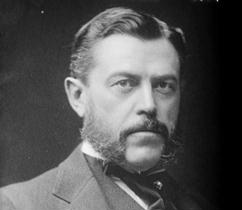

One of the most successful wheeler-dealers of all time -- the man who

created IBM -- remembers how difficult it was to sell the Wright

airplane. Flint is best remembered as the "father of trusts" -- he

invented the corporate conglomerate. He believed that smaller companies,

each with unique ideas and assents, could be combined to make large,

stronger, and more profitable organizations. He proved this by bringing

together companies to found U.S. Rubber (1892), American Woolen (1899)

and the company that would become International Business Machines

(1911).Flint also put together other famous deals, and perhaps his most

famous was the sale and licensing of the Wright airplane to investors in

Europe.

|

Charles Ranlett Flint.

|

|

It's amazing how many bad ideas a group of aeronautical engineers can

generate when they really put their minds to it. This was especially

true in the earliest days of aviation when no one really knew what an

airplane should look like. Over the years, we've collected a large

assortments of "flops" – aircraft built in the pioneer era of aviation

that never got off the ground. Some were simple constructions, some were

absurdly complex, some looked nothing at all like an airplane. They all

shared one common trait – the were intended to fly, but never did.

|

You can wind it up, but it won't take you anywhere.

|

|

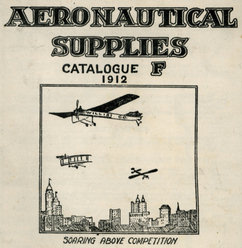

A mail-order catalogue for the discerning 1912 pilot and

aircraft-builder – engines, tires, fitting, goggles, even plans for a

Bleriot XI – an amazing 20 pages of industrial aviation stuff from a

time when the aviation industry was only 3 years old! |

Great prices, too.

|

|

The newly formed Aero Club of America hosts a trade show in New York

City, showing the very latest in aviation equipment from both sides of

the Atlantic Ocean, including the crankshaft and flywheel from the

"fabled" Wright Flyer. This unique trade show, the first

of its kind in America, was a pivotal event for the Wright brothers and

American aviation. Although they did not attend personally, the show

started an important ball rolling. Before the show, there was little to

distinguish the Wrights from the dozens of scientists, entrepreneurs,

and crackpots who claimed they were close to solving the "flying

problem." But the show attracted the attention of some powerful men who,

after some investigation, found that the Wrights had indeed solved it.

|

A turning point in American aviation.

|

|

|

|