|

Up

Up

Wright

Wright

Bicycles

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

efore they built

airplanes, the Wright brothers built bicycles. Like so many Americans in the

early 1890s, they embraced the bicycle craze that swept the country in the wake

of the invention of the "safety bicycle" – a bicycle with two

equal-size wheels, front and back. This design was much easier to mount and ride

than the "ordinary bicycle," which we now remember as the high-wheel

bicycle. efore they built

airplanes, the Wright brothers built bicycles. Like so many Americans in the

early 1890s, they embraced the bicycle craze that swept the country in the wake

of the invention of the "safety bicycle" – a bicycle with two

equal-size wheels, front and back. This design was much easier to mount and ride

than the "ordinary bicycle," which we now remember as the high-wheel

bicycle.

First Bicycles

Wilbur Wright bought a used high wheel ordinary bicycle for just $3

while the Wright family lived in Richmond, IN between 1881 and 1884. In

1892, Orville bought a new Columbia safety bicycle for $160. In the same

year, Wilbur purchased a used Eagle safety bicycle for $80. Both enjoyed

cross-country cycling and Orville would occasionally enter races. He

once won a rocking chair in a race at the Montgomery County Fair.

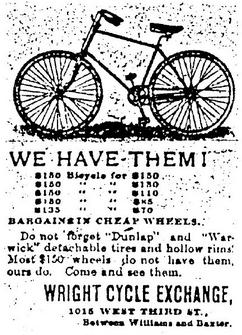

First Bicycle Shop

The Wrights opened a bicycle sales and repair shop called the Wright

Cycle Exchange at 1005 West Third Street in Dayton, OH in 1892. They

carried many brands of bicycles, including Fleetwing, Reading, Coventry

Cross, Envoy, Smalley, Warwick, Duchess, and Halladay-Temple. Prices

ranged from $40 to $100. The Wrights also rented bicycles and sold parts

and accessories. It's probably not an accident that the Wrights decided to

open in 1892 or that they chose a location on West Third Street. The

League of American Wheelmen held their twelfth annual meet in Dayton

on July 4 and 5, 1892. It was a huge event with thousands of

cyclists visiting the city to compete in thirteen different races

for prizes worth up to $500. The visiting cyclists were also invited

to tour the city and by far the most popular destination was the

Central National Soldiers Home with its exquisitely landscaped

grounds. The Soldiers Home was west of Dayton along Dayton-Eaton

Pike, better known as West Third Street. The Wheelmen would have

passed right by the Wright Cycle Exchange on their way to and from

the Soldiers Home. Bicycle Shop Locations and Names

As their business grew, the Wright brothers moved their bicycle shop

six times and changed the name once.

- 1892 – Wright Cycle Exchange at 1005 West Third Street, Dayton, OH.

- 1893 – Wright Cycle Exchange at 1015 West Third Street, Dayton, OH.

- 1893 to 1894 – Wright Cycle Exchange at 1034 West Third Street. The

name was later changed to Wright Cycle Co.

- 1895 to 1897 -- Wright Cycle Co. at two locations – the

main

store at 22 South Williams Street, Dayton, OH and a branch in

downtown Dayton at 20 West Second Street. The branch store was

closed in 1896.

- 1897 to 1908 – The Wright Cycle Co. at 1127 West Third Street,

Dayton, OH.

Manufacturing Bicycles

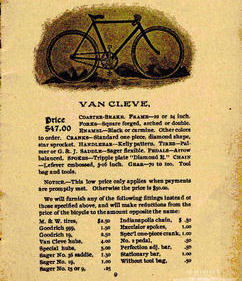

In late 1895, the Wrights began to make preparations to manufacture

their own bicycles. They introduced the

"Van Cleve" on April 24,

1896. The Van Cleves, ancestors of the Wrights, had been among Dayton's first settlers,

arriving in 1796. Dayton was about to celebrate its centennial in 1896

and historical awareness was high – it was a good choice for a brand

name. Later in the year, the

Wrights introduced a second, less expensive model called the "St.

Clair." Again, the name was drawn from local history; Arthur St.

Clair had been the first president of the Northwest Territory, which later

became Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

The term "manufacture" is used loosely here, as it is in most Wright

biographies. Both the Van Cleve and the St. Clair bicycle were largely

assembled from parts made elsewhere. Frames, handlebars, seats, cranks,

and tires were purchased from sources such as the Davis Sewing Machine

Company of Dayton, OH (which later became the Huffy Corporation), Sager

Manufacturing Company of Rochester, NY, and Pope Manufacturing of

Hartford, CT. The only parts the Wrights were known to have made from

scratch were their bicycle wheel hubs. The Van Cleve was built around a

tall frame, possibly intended for racing, and sold for $65 when

introduced. The St. Clair had a shorter frame, was easier to mount, and

was initially priced at $42.50. During their peak years of

production, between 1896 and 1900, the Wrights manufactured about 300

bicycles.

There is some controversy over whether or not the Wrights manufactured

a bicycle called the "Wright Special." The only reference the

Wrights made to this bicycle was in an announcement that appeared

April 17, 1896: "For a number of months, the Wright Cycle Co.

have been making plans to manufacture bicycles...we will have several

samples out in a week or ten days, and will be ready to fill orders before

the middle of next month. The WRIGHT SPECIAL will contain nothing but high

grade material. " But the Wright Special never materialized. The bicycle the Wrights unveiled seven days later was the Van Cleve.

The name "Wright Special" appears in none of their

advertisements or catalogs from this

time, so it's reasonable to assume that the Van Cleve was the "special"

bicycle the Wrights had advertised. In their

1900 catalogue,

the Wrights dropped the St. Clair line and recast their entire

offering under the Van Cleve brand. The catalog refers to a "Standard"

and a "Special" model of their Van Cleve bicycle. The Standard

model had parts of higher quality than the

Special, but both models were Van Cleves. The Standard Van Cleve was

now $47. The Special Van Cleve bicycle, with its economical

components, sold for

$32. Furthermore, the customer could request

other available parts and expect an adjustment in the price. The notations of "Special" in the bicycle shop ledger

most probably record

a customer's request for the least expensive option described in the

Van Cleve catalogue; they do not indicate a

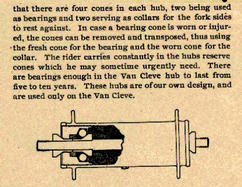

different brand. Upgrades

During the years the Wright brothers were assembling bicycles, they

constantly improved their product to keep it at the cutting edge of

evolving cycling technology. The Van Cleve featured a wheel hub with

three unique features. First, the bearings were adjusted by screwing the

inner bearing races or "cups" in or out of the hub. (Most hub bearings were adjusted by

tightening nuts on the axle.) The advantage of the Wright hub, according

to the Van Cleve catalog, was “…the wheels can be removed from the frame

and replaced…without changing the adjustment of the bearings.”

Second, the bearings were sealed with felt washers. Dayton only had 12

miles of paved streets in those days and the dust played havoc with

bicycle bearings, causing them to wear quickly. The washers not only

kept the dust out, they created a reservoir inside the hub that bathed

the bearings in oil. “They are absolutely dust proof, and oil retaining

to such a degree that only one oiling in two years is all they require.”

Third, each hub carried it's own spar parts – two extra outer bearing

races or "cones" on which the bearings rode. These were likely parts to

wear out on early bicycles. “In case a bearing cone is worn or injured,

these can be removed and transposed…”

The "coaster brake," an internal

friction brake inside the rear hub that was activated by back-pedaling,

first appeared in 1898. It seems to have been simultaneously

invented by several people – Harry P. Townsend, of the New Departure

Manufacturing Co, James S. Copeland of the Pope Manufacturing Co.,

and William Robinson of Brooklyn, New York all filed for patents

within a year of each other. That same year – 1898 – the

Wrights designed their own version of the coaster brake that would

work with their special wheel hubs. They

contracted with Charley Taylor, a local machinist, to make the brake

parts. The brothers would hire Charley in 1901, and in 1903 he would

help them to build their first aircraft engine.

In 1900, the Wrights announced a "bicycle pedal that can't come

unscrewed." Pedals were mounted to the crank by threaded spindles.

On early bicycles, both crank arms had standard right-hand threads. As

the cyclist pedaled, the action tended to tighten one pedal and loosen the

other, with the result that one pedal kept dropping off the bike. British

inventor William Kemp Starley had solved a similar problem years before when

the right-hand cups that housed the crank or "bottom" bearing on early

bicycles kept coming loose. He simply reversed the thread direction on

the right cup so the pedaling action kept it tight. It wasn't long

before bicycle makers realized the same solution could keep the pedals

in place. Wilbur

and Orville were in the vanguard of those manufacturers that offered right-hand threads on one

crank arm and left-hand

threads on the other.

Business Profits

The bicycle business was good to the Wright brothers, initially. In

their best year (1897), they made $3000 or $1500 apiece in a time when the

average American worker was doing well to make $500 per year. They also

managed to save $5000, which went a long way in financing their aviation

experiments. However, this market wasn't to last. Beginning in 1898,

there began a serious shakeout among small bicycle manufacturers as

they either closed up or sold out to larger businesses. The world

bicycle market had been saturated

by thousands of small assembly firms that had sprung up to satisfy the initial rush

to own a bicycle. These thrived until huge manufacturing firms geared up

for mass production, selling bikes for as little as $10 apiece by the turn of the

century. At the same time, they bought up many smaller businesses,

eliminating competition – the Wrights refer to this state of affairs in

the introduction to their

1900 catalogue. To

remain competitive, the Wrights were forced to lower

their prices and consolidate. Their 1900 catalog showcases the one

remaining advantage they had over big manufacturers, the Wrights'

ability to build customized bicycles. Clients could choose

different cranksets, forks, handlebars, saddles, and pedals to suit,

or add features such as fenders, chain guards, and brakes. The

Wright brothers built Van Cleves to order. It's interesting to

note that in the very same year the Wright bicycle business began to

decline (1898), Assistant Secretary to the Navy Theodore Roosevelt

convinced the War Department to pay Secretary of the Smithsonian

Institution

Samuel Langley $50,000 to develop his 1896

Aerodrome into a

man-carrying flying machine. Although this was supposed to be a

secret, the amount was the largest sum ever paid by the War

Department to develop a weapon and the news soon leaked. Wilbur and

Orville were already studying the "flight problem" and knew that all

aircraft to date had inadequate controls. Langley's aerodromes had

none at all. A year later the brothers would begin research in

earnest with the express goal of developing an aircraft control

system. Although none of their biographies discuss the Wrights'

financial motives, its not unreasonable to assume that the Wrights

saw in this news a way to survive the coming shakeout. If Langley

was successful, the War Department would need a control system to

make their flying machine practical. They came close to abandoning

this plan, however. In mid-1902, after testing two unsuccessful

gliders in 1900 and 1901, Wilbur confided to his friend

Octave Chanute that the bicycle business was declining and he

was looking for another manufacturing line. Chanute suggested small

heaters for carriages or electric refrigerators. Fortunately, just a

few months later the Wrights flew their 1902 glider and made the

aeronautical breakthrough that kept them focused on airplanes. Selling the Business

The Wright manufactured very few bicycles after 1902 and none

after 1904 – they were much too busy developing their airplanes and trying to find a

market for them. When they finally began to sell aircraft in

1909, the bicycle shop at 1127 West Third Street was converted to a

machine shop where employees of the Wright Company – the brothers'

airplane manufacturing business – turned out parts for the airplane

engines and drive trains.

In 1909 or 1910, the Wrights sold all their remaining bicycle parts and

the rights to the Van Cleve name to W.F. Meyers, a bicycle salesman,

repairman, and machinist. Meyers did not make his own bicycles, but had

another company put them together and he put the Van Cleve nameplate on

them. Meyers continued to sell Van Cleve bicycles until 1939.

Existing Wright Bicycles

While the Wrights are thought to have manufactured several

hundred bicycles between 1896 and 1904, only five still exist:

- A St. Clair, manufactured before 1900, currently at the National Air & Space

Museum in Washington DC. (It's on loan from The Henry Ford.)

- Two Van Cleves, both manufactured after 1900, at Carillon Park in Dayton, Ohio.

- A Van Cleve, probably manufactured after 1900, at the National Museum of the United

States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. (This is the only known

example of a women's bicycle built by the Wrights.)

- A Van Cleve, manufactured prior to 1900, at Greenfield Village, part of The Henry

Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

In Their Own

Words

- 1900 Wright Van Cleve

Bicycle Catalogue – A 12-page catalogue, written and

produced by the Wright brothers, explaining the virtues of their

built-to-order bicycles. The catalogue was printed in the Wrights'

print shop, just across the street from the Wright bicycle shop.

A Closer Look

- The Wright Van Cleve,

circa 1897 – The kind and helpful curators at The Henry Ford

museum and Greenfield Village let us inspect the oldest remaining

Wright bicycle.

|

This newspaper ad for the Wright Cycle exchange

appeared in 1893.

The third Wright bicycle shop at 1034 West Third

Street. It was at this location that the Wrights changed the name of their

business to the Wright Cycle Co.

The Wright Cycle Co. at 1127 West Third Street,

where the Wrights built gliders and airplanes.

Orville and a helper at work in the Wright Cycle Co. shop at 22

South Williams Street in 1897.

A Wright Van Cleve bicycle,

built prior to 1900. It was a tall bike by modern standards; the

horizontal bar was 36-1/2" off the ground. Van Cleves built after 1900

had frames more than 4" shorter.

A Wright Van Cleve built after 1900. This was the

"Special" economical model. The horizontal wheel is

part of an aeronautical experiment from 1901.

The badge for the Wright Van Cleve, circa 1897. The

log cabin represents Newcomb’s Tavern, which was and continues to be the

oldest building in Dayton, Ohio. The tavern was built in 1796, the same

year Dayton was founded, then was rediscovered in 1894 and restored in

1896 just in time for Dayton’s centennial celebration – the same year

the Wrights began assembling their own bicycles.

1897 newspaper ad for Wright Van Cleve bicycles.

"Van Cleves get there first," was a play on words, but you had to know

local history to get the joke. The Wright's great-great-grandmother,

Catherine Van Cleve Thompson, and her daughter Mary Van Cleve had been the first

to step ashore from a boat of settlers that had traveled upriver from

Cincinnati in 1796

to the site where Dayton was built.

A section in the 1900 Wright Van Cleve

catalog, describing the Wrights special wheel hub.

For a short time in 1909 and 1910, the Wright bike shop was

converted to a machine shop for making airplane parts.

A Meyers Van Cleve made in the 1930s.

A page from the Wright Van Cleve catalog.

The Wright Van Cleve on display at Greenfield Village.

|