|

Up

Up

Pilots,

Pilots,

Planes

and Pioneers

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

hile

the Wright brothers may have been the first to make a sustained,

controlled flight, they were just two among hundreds of brave men and

women who helped to give the world its wings during the earliest days of

aviation. Their Flyer was but one of many historically important aircraft. Below are brief

descriptions and photos of some of the most important

people and planes, and where available resources and links where you can find more

information. In some cases, contributors have supplied expanded

histories and biographies. Those are listed at the right and linked below. hile

the Wright brothers may have been the first to make a sustained,

controlled flight, they were just two among hundreds of brave men and

women who helped to give the world its wings during the earliest days of

aviation. Their Flyer was but one of many historically important aircraft. Below are brief

descriptions and photos of some of the most important

people and planes, and where available resources and links where you can find more

information. In some cases, contributors have supplied expanded

histories and biographies. Those are listed at the right and linked below.

A

B

B

C

C

D

D

E

E

F

F

G

G

H

H

I

I

J

J

K

K

L

L

M

M

N

O

O

P

P

Q

Q

R

R

S

S

T

T

U

U

V

V

W

W

X

X

Y

Y

Z

Z

|

|

|

|

|

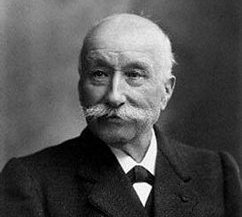

Clement

Ader of France was a distinguished electrical engineer who helped

pioneer the telephone. He also studied birds and bats, and in 1873 built a bird-shaped glider with feathered wings.

He made a few

tethered accents, then began thinking about powered flight. In 1882, he

began work on an airplane and a lightweight steam engine to power it. He

called his craft the Eole. It had a 20-horsepower engine,

bat-like wings, no rudder, and no elevator. When tested in

1890, the 653-pound (296-kilogram) craft flew about 165 feet (50

meters) at a height of 8

inches (20 centimeters) off the ground. It was the first aircraft to take off from level

ground under its own power. In 1892, Ader convinced the French

Ministry of War to fund further research. He built a twin-engine craft

called the Avion III, and attempted to fly it before official observers in

1897. It failed to impress those observers, and they cut off

funding. Later, after Alberto Santos-Dumont had made a short flight in

France, Ader began to claim that his craft had flown almost 1000 feet (304

meters) in

1897. The official report, released many years after the test, says

nothing of the kind. It records that the Avion III never completely left the

ground, although one or two of its three wheels may have come off.

See also:

Airmen

& Chauffeurs. |

Clement Ader

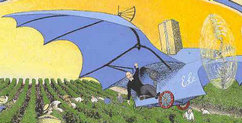

An artist's conception of the Eole

in flight. The actual "flight" was just inches above the ground.

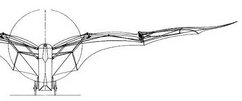

Plans for the Eole.

|

The Avion III, on display in

Paris, France.

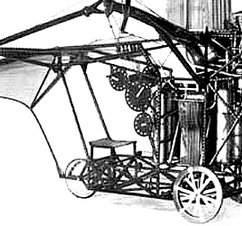

An uncovered model of the Eole,

showing the bat-like frame of the aircraft.

|

|

|

"Aerodrome A" was a manned

aircraft commissioned by the U.S. Army in 1898. Originally, it was

intended to be used in America's war with Spain, but the

Spanish-American War was over by the time the U.S. War Department's Board of

Ordinance awarded the Smithsonian Institution $50,000 to build a

man-carrying airplane. It was hoped that it might be useful in

future wars or in defense.

Samuel P. Langley,

then Secretary of the Smithsonian, headed the project. The aircraft,

also known as the Great Aerodrome, was based on the designs of

smaller tandem-wing powered "aerodromes" that Langley has flown

successfully beginning in 1896. Originally, it was planned to

test-fly the Aerodrome in 1901, but problems – especially with the

motor – delayed the test until 1903. Langley also built a

quarter-scale version of the Aerodrome to test the soundness of the

design. He tried and failed to fly the model in 1901, but it

eventually achieved a successful flight in August 1903, making it

the first gasoline-powered aircraft ever to fly, albeit unmanned. The full-scale

Aerodrome was ready for testing in October of that year. It was a

massive aircraft for its day, with a wingspan of 48 feet (14.8

meters) and a length of 52 feet (16 meters). It weighed 750 pounds

(340 kilograms), and had a remarkable five-cylinder radial engine

producing up to 52 horsepower. The Aerodrome was to be piloted by

Charles

Manly, who also headed the construction team and built the engine.

It had no roll control, but it was pitched up and down by a pivoting

tail and yawed right and left by a "steering rudder" amidships.

It was intended to be launched by a catapult from the roof of a

large houseboat, which doubled as a workshop and storage shed.

Langley tried twice to fly the Aerodrome, on 7 October and 8

December 1903. It failed both times, dropping into the Potomac River

just south of Washington DC. Langley maintained that the Aerodrome

could have flown but was snagged by the catapult on both attempts.

Langley died in 1906. The Aerodrome remained in storage until 1914

when Charles D. Walcott, then Secretary of the Smithsonian, sent the

remains to Glenn Curtiss in Hammondsport, NY for further tests.

Curtiss made significant changes to the airframe, wings, engine, and

controls, then managed several hop-flights on 28 May, 2 June, and 5 June

1914. Further changes, including a more powerful motor and modern

propeller, eventually enabled the Aerodrome to fly for 20

miles. Curtiss and the Smithsonian claimed that these flights proved

the Aerodrome was airworthy in 1903 and could have flown before the

Wright brothers. It was restored to its original configuration and

displayed at the Smithsonian in 1918 with a plaque that identified

it as the the first powered airplane "capable of sustained flight."

This angered Orville Wright who asked the Smithsonian to admit they

made significant changes to the aircraft and retract their claims.

When they declined to do so, he sent the 1903 Wright Flyer to the

Science Museum in Kensington, England in 1928 in protest. The

Smithsonian eventually recanted, and the Flyer was returned to

America in 1948. The Langley Aerodrome is now on display at the

Smithsonian's Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA. For an

expanded history of the Aerodrome A and its test flights,

see

The Wright/Smithsonian Controversy.

|

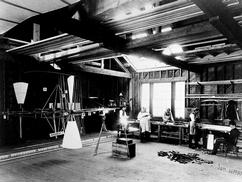

The Aerodrome was built in Langley's workshop in the "South Shed"

annex to the Smithsonian.

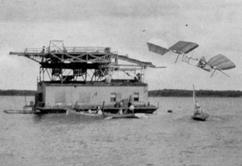

The Aerodrome was launched from a houseboat floating on the Potomac

River, south of Washington DC.

The first launch attempt on 7 October 1903. The aircraft simply slid

into the water.

The Aerodrome in the Potomac River after the 7 October 1903 launch

attempt.

The Aerodrome in flight over Lake Keuka near Hammondsport in

September

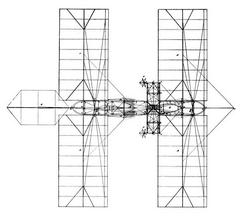

A three view of the Langley

Aerodrome A.

|

The airframe of the Aerodrome, showing the cockpit, engine, and

tail. By shifting his weight along the bench, the pilot could adjust

the aircraft's center of gravity.

The Aerodrome in place on its catapult. Giant springs shot the

aircraft forward, then released it over the water.

The second launch attempt on 8 December 1903. This time the back

wings collapsed.

The Aerodrome being fitted for pontoons at the Curtiss Aeroplane and

Motor Company in 1914. Curtiss did away with the catapult and

launched the Aerodrome from the water like a seaplane.

The Langley Aerodrome A was

restored to its original 1903 configuration and now hangs in the

Udvar-Hazy Center, an annex to the Air and Space Museum.

To see an interactive 3D model of Aerodrome A, click

HERE or on the illustration above. You must have a recent Adobe

Reader plug-in (Version 9.0 or later) to view this model.

|

|

Ernest Archdeacon

of France was wealthy lawyer, sportsman, and aviation enthusiast. He built

several experimental gliders, mostly based on Wright designs. More

important, he offered several lucrative prizes to encourage the

development of aviation, especially in France. In May 1903, he and

Ferdinand Ferber created the Aviation Committee in the Aero Club

du France to kindle French interest in heavier-than-air

flight. His hope was to encourage young French aviators to more daring

deeds and beat the Americans – in particular, the Wright brothers – into

the air.

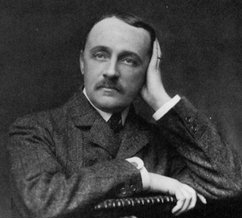

|

Ernest Archdeacon

|

The 1905 Archdeacon floatplane-glider was designed by Archdeacon,

but built and flown by Gabriel Voison.

|

|

William Avery

of Chicago, Illinois was a carpenter and electrician when he began

working for

Octave

Chanute in 1895. He

helped build several gliders, including the multi-winged Katydid,

then joined Chanute's band of aviation enthusiasts at the Indiana Dunes to test

the aircraft in the summer of 1896. He was among those who flew the

Chanute-Herring biplane glider, a design which had a huge impact on

early aviation. He also built a glider for

Augustus

Herring and Mathias Arnot and helped test it in 1897. In 1904, he

built an updated version of Chanute's 1896 biplane glider, then made

over forty flights

at the St. Louis World's Fair – one of the first public exhibitions

of gliding flight in America.

|

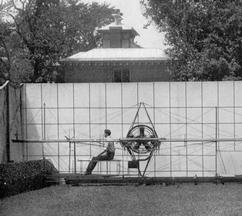

Avery's Katydid at the

Indiana Dunes in the summer of 1896. The wings of this unique

aircraft could be removed and rearranged to adjust the position of

the center of lift. In this manner, Chanute and his associates hoped

to find a stable configuration.

|

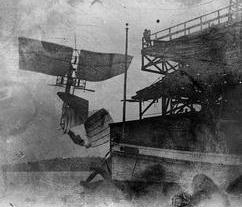

Avery about to launch a Chanute-designed biplane glider in St. Louis in 1904.

The glider followed the same lines as the 1896 Chanute-Herring

glider, but its camber and wing structure were closer to the Wright

gliders Chanute had seen fly at Kitty Hawk in 1901 and 1902.

|

|

|

|

|