|

Up

Up

Pilots,

Pilots,

Planes

and Pioneers

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

hile

the Wright brothers may have been the first to make a sustained,

controlled flight, they were just two among hundreds of brave men

and women who helped to give the world its wings during the earliest

days of aviation. Their Flyer was but one of many historically

important aircraft. Below are brief descriptions and photos of some

of the most important people and planes, and where available

resources and links where you can find more information. In some

cases, contributors have supplied expanded

histories and biographies. Those are listed at the right and linked below. hile

the Wright brothers may have been the first to make a sustained,

controlled flight, they were just two among hundreds of brave men

and women who helped to give the world its wings during the earliest

days of aviation. Their Flyer was but one of many historically

important aircraft. Below are brief descriptions and photos of some

of the most important people and planes, and where available

resources and links where you can find more information. In some

cases, contributors have supplied expanded

histories and biographies. Those are listed at the right and linked below.

A

B

B

C

C

D

D

E

E

F

F

G

G

H

H

I

I

J

J

K

K

L

L

M

M

N

O

O

P

P

Q

Q

R

R

S

S

T

T

U

U

V

V

W

W

X

X

Y

Y

Z

Z

|

|

|

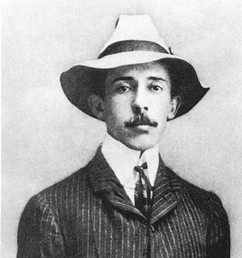

Alberto Santos Dumont was born in Brazil, then

emigrated to France in 1891 with his parents and the profits of their

coffee plantation. A dapper playboy, a talented mechanic, and a natural

engineer, he began racing motorized tricycles, then turned to ballooning,

then to dirigibles. He delighted Parisians by dropping down unexpectedly

from the skies in his primitive gasbags to salute the President of France,

attend a children's birthday party, or just enjoy a cup of coffee.

In 1901, he piloted his Airship No. 6 around the Eiffel Tower, winning a

prize of 100,000 francs -- all of which he gave to his mechanics.

In 1904 -- a year after the Wright brothers had made their first

powered flight-- Santos Dumont turned his attention to heavier-than-air

flying. He began with a glider, then built an unsuccessful helicopter in

1905. In 1906, he built a strange-looking flying machine -- a

tail-first pusher biplane of what the French had begun to call the type du Wright, loosely

based on the Wright biplane plans that had been published in

several European magazines. His design was influenced by other sources as

well; the wings were set in a pronounced dihedral like Penaud models and

divided into "cells" with side curtains like a

Hargrave kite. The box-like elevator and rudder protruded in

front of the wings like the head of a duck in flight. It was promptly

dubbed a canard (French for "duck"), and the name was

incorporated into the growing aeronautical lexicon.

Santos Dumont called the airplane the 14-bis, meaning

"14-encore" since the airplane made its first appearance

suspended from the belly of Santos Dumont's No. 14 dirigible. He

flew it without the dirigible on 13 September 1906, making a hop of

between 23 and 43 feet (7 and 13 meters), depending on who you talked to. On

27 October, he

managed to fly 197 feet (60 meters). Then, on 12 November, he set the

first aviation record in Europe, flying 722 feet (220 meters) in

21-1/2 seconds with members of the Aero-Club du France in

attendance. This won Santos Dumont a prize of 1500 francs for making the

first flight in Europe over 100 meters, and because he was observed

by officials from what would become the Federation Aeronautique

Internationale (the designated keeper of aviation records), he was

credited with making the first official powered flight in Europe.

Santos Dumont flew the 14-bis for one more brief hop on 4 April

1907, then abandoned it as a technological dead end. He turned the design

around so the canard was in back and made a tractor biplane with plywood

wings, the 15-bis. This, however, refused to fly. He built one more

dirigible -- actually a marriage of a dirigible and an airplane, the No.

16. This, unfortunately was destroyed on the ground before it could

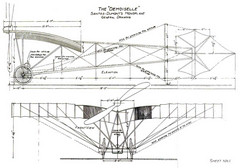

be test flown. Then he turned to monoplanes and produced three

unsuccessful models, but the fourth – No. 19 or the Demoiselle,

first flown in 1909 – was a winner. Tiny and quick, it was the first

practical light aircraft, although pilots reported that it was a handful

in the air. In a grand and magnanimous gesture, Santos-Dumont

offered the plans to the public free of charge. They were published

worldwide – in America, they appeared in Popular Mechanics – enabling

hopeful young aviators of limited means to get into the air inexpensively.

In this way, Santos Dumont and his Demoiselle helped fuel the

phenomenal growth of aviation in the years before World War I.

Unfortunately, the Demoiselle was Santos Dumont's swan song .

Shortly after its introduction, he was stricken with multiple

sclerosis, dropped out of aviation, and retired to Brazil in 1916. He

committed suicide there in 1932.

For a discussion of the controversy caused by Brazil's insistence that

Santos Dumont deserves the title of first to fly, see also

Santos Dumont.

|

Alberto Santos Dumont.

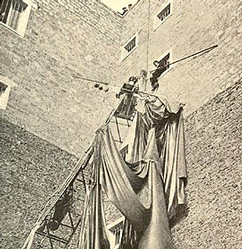

Not at of Santos Dumont's airship adventures ended well. During a

flight in 1901, he collided with a tall building and had to be

rescued.

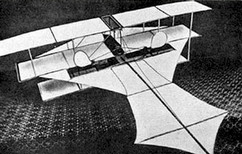

Santos Dumont tests the controls of his first aircraft with it

suspended from his No. 14

airship.

Santos Dumont obtained a 50 hp engine and on 13 September 1906, flew

the 14 bis for the first

time.

The 15 bis looked similar to

the 14 bis, but was intended

to fly with

its wings forward.

After the failure of the 15 bis, Santos Dumont designed a small

monoplane. By 1909, he had developed a practical airplane he called

the Demoiselle (dragonfly).

Santos Dumont piloting the Demoiselle in 1909.

|

Santos Dumont at the controls of one of his early airships.

Santos Dumont in his No. 6

rounds the Eiffel Tower on his way to winning the Deutsch Prize in

1901.

Walking the 14 bis through

the streets of Paris on 21 August 1906. The first attempt to fly was

unsuccessful; with only a 24-horsepower engine the airplane was

underpowered.

An operational replica of the 14

bis in flight in Brazil.

Santos Dumont managed a short hop in the

15 bis in 1907, but it ended

badly.

Santos Dumont did not patent the Demoiselle, but instead shared the

design with the world. These plans were published in 1910

issue of Popular Mechanics.

A restored Demoiselle.

|

|

George Spratt

of Pennsylvania was a doctor turned aeronautical enthusiast and scientist.

He contacted Octave Chanute in 1899, writing him about an apparatus he has

designed to measure the lift of air foils and his model glider. He had

some success with the lift-measuring device but none with the glider.

Chanute wangled Spratt an invitation to visit the Wright in Kitty Hawk in

1901 and watch them fly. The Wrights liked Spratt, and he and Orville

spent much time discussing various ways to measure lift and drag. Some of

Spratt's ideas were incorporated in the "drift balance," an

instrument they used to find the ratio of lift to drag, in the winter of

1901 and 1902. Spratt also visited the Wrights at Kitty Hawk in 1902 and

1903, and corresponded with both Wilbur and Orville over many years.

Spratt went on to develop a stall-proof, spin-proof airplane design

called the "Control Wing." It featured a unique method

of aircraft control. The main wing was "floating" – the pilot

changed the angle of incidence to climb, descend, and turn. Spratt

also pioneered the triangle-shaped "control bar," now used on

many hang gliders.

|

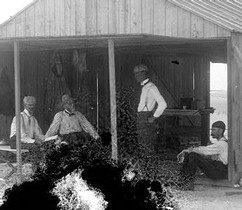

George Spratt first visited the Wrights in 1901 at their camp in

Kitty Hawk. He's seated on the far Wright, behind Wilbur.

George Spratt flying and early model of his "Control Wing" aircraft.

|

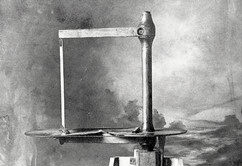

Spratt's "tangential measuring machine" measured the ratio of lift

to drag. The Wrights' "drift balance" performed the same task, but

the mechanism was different.

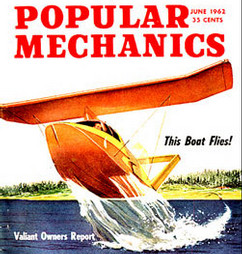

This flying boat on the June 1962 cover of

Popular Mechanics features a

Spratt floating wing.

|

|

John Stringfellow designed a

lightweight 30-horsepower steam engine for

Samuel Henson's 1843 Aerial

Steam Carriage and became his partner in the Aerial Transit Company. After

their first model failed to fly in 1847 and Henson left for America, Stringfellow carried on for a short time and built and improved

model with a better engine. Reports are contradictory as to whether this

model actually flew, but it's clear that it did better the the first.

Stringfellow made his last model in 1868 – a triplane which could only

make descending glides and could not sustain itself in flight. However,

the design itself was extremely influential and became the model for the

successful biplanes and triplanes that would follow.

Also see:

The First Airplanes

and Powering Up.

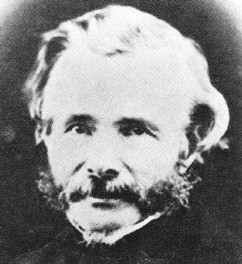

|

John Stringfellow.

Stringfellow's monoplane, first tested in 1848, is considered by

some historians to be the first successful powered flying machine.

|

Stringfellow designed this light-weight steam engine to power his

models.

Stringfellow's triplane model was displayed at the Crystal Palace in

London in 1868 and influenced aircraft design for decades

afterwards.

|