|

Up

Up

1903 Engine

1903 Engine

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

nce

they had decided to attempt powered flight, the

Wrights calculated they needed an engine that produced at least 8 horsepower

and weighed no more than 200 pounds (91 kilograms). A quick survey

of the automotive market showed there was no such engine available

and they would have to make their own. An acquaintance at the nearby

Buckeye Irons and Brass Works advised then that they could save

weight if they cast the engine block from aluminum. Although this

was a soft metal, alloys had recently been developed that were much

stronger – both Benz and Daimler

in Germany were successfully making engines with aluminum blocks.

The Wrights decided to cast the block from an alloy of 92% aluminum

and 8% copper. nce

they had decided to attempt powered flight, the

Wrights calculated they needed an engine that produced at least 8 horsepower

and weighed no more than 200 pounds (91 kilograms). A quick survey

of the automotive market showed there was no such engine available

and they would have to make their own. An acquaintance at the nearby

Buckeye Irons and Brass Works advised then that they could save

weight if they cast the engine block from aluminum. Although this

was a soft metal, alloys had recently been developed that were much

stronger – both Benz and Daimler

in Germany were successfully making engines with aluminum blocks.

The Wrights decided to cast the block from an alloy of 92% aluminum

and 8% copper.

After the castings had been made the Wrights "mechanician,"

Charlie Taylor, machined the parts and assembled the engine. He

later described his work:

"We didn’t make any drawings. One of us would sketch out the part

we were talking about on a piece of scratch paper, and I’d spike the

sketch over my bench. It took me six weeks to make that engine. The

only metal-working machines we had were a lathe and a drill press,

run by belts from the stationary gas engine.

"The crankshaft was made out of a block of machine steel 6 by 31

inches and 1-5/8 inch thick. I traced the outline on the slab, then

drilled through with the drill press until I could knock out the

surplus pieces with a hammer and chisel. Then I put it in the lathe

and turned it down to size and smoothness.

"The body of the first engine was of cast aluminum and was bored

out on the lathe for independent cylinders. The pistons were cast

iron, and these were turned down and grooved for piston rings.

"The completed engine weighed 180 pounds and developed 12

horsepower at 1,025 revolutions per minute. [It actually produced

nearly 16 hp when it was first started, by this dropped to 12 hp as

the engine heated up.]

"...The fuel system was simple. A one-gallon fuel tank [it

actually held just 22 ounces] was

suspended from a wing strut, and the gasoline fed by gravity down a

tube to the engine. The fuel valve was an ordinary gaslight pet

cock. There was no carburetor as we know it today. The fuel was fed

into a shallow chamber in the manifold. Raw gas blended with air in

this chamber, which was next to the cylinders and heated up rather

quickly, this helping to vaporize the mixture. The engine was

started by priming each cylinder with a few drops of raw gas.

"The ignition was the make-and-break type. No spark plugs. The

spark was made by the opening and closing of two contact points

inside the combustion chamber. These were operated by shafts and

cams geared to the main camshaft. The ignition switch was an

ordinary single-throw knife switch we bought at the hardware store.

Dry batteries were used for starting the engine, and then we

switched onto a magneto bought from the Dayton Electric Company.

There was no battery on the plane.

"Several lengths of speaking tube, such as you find in apartment

houses, were used in the radiator.

Other features included a bicycle chain turned the camshaft which

operating the spark breaker arms and exhaust valves, but the

"automatic" intake valves were opened by suction. Having no

throttle, the motor only ran at full speed, tuned with a lever that

adjusted the camshaft timing. A splash system lubricated the

bearings and other moving parts in the crankcase, while a small

gear-driven oil pump supplied oil to a tube that that dripped into

the cylinders and onto the pistons.

The engine was first run on 12 February 1903. The very next day

it overheated and seized up on the bench during a test run. New

castings arrived from the foundry on 20 April 1903 and Charlie had

the engine rebuilt and ready to go by early June.

After powering the Flyer on four flights at Kitty Hawk on 17

December 1903, the engine was seriously damaged when wind overturned

the Flyer. Today, the original cast aluminum engine block is

displayed at the museum attached to the Wright Brothers Monument at Kitty Hawk,

NC. The

Wrights sent the crankshaft and flywheel to be displayed at the

Aero Club of America Exhibition of Aeronautical Apparatus in New

York in 1906, and the parts were never returned. The engine now

on display in the 1903 Wright Flyer at the Smithsonian Institution was

built in 1916 when Orville restored the Flyer for an exhibition at

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Orville used some original parts

(we don't know which or how many), but he made much of the engine anew.

Specifications:

- Cylinders: 4

- Stroke: 4 in (10.2 cm)

- Bore: 4 in (10.2 cm)

- Displacement: 201 in3 (3.3 l3)

- Horsepower:12

- Ignition: Make-and-brake powered by low-tension (10-volt)

magneto.

- Weight: 180 lbs (81.6 kg)

- Unique features: Aluminum block, no carburetor.

References:

- McFarland, Marvin W. (ed) The papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright. McGraw-Hill

Book Co., New York, 1953, pp 1210-1214, plates 225-226.

- Hobbs, Leonard S. The Wright Brothers' Engines and Their design. Washington, D.C.:

Smithsonian Institution Press, 1971, pp 9-28.

- Lippincott, Harvey H. Propulsion System of the Wright Brothers. In Wolko, Howard S.

(editor), The Wright Flyer, an Engineering Perspective. The Smithsonian Institution Press,

1987, pp 82-86.

[Submitted by Joe W. McDaniel]

|

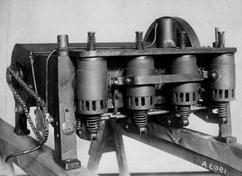

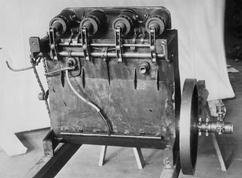

The 1903 Wright engine on a test bench after it was restored in

1916.

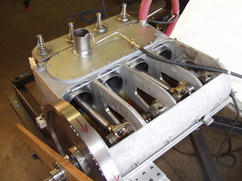

The 1903 engine mounted in the Wright Flyer during restoration.

As the engine heated up, the firing chambers on the left side of the

engine – nearest the

pilot – would glow red

hot.

The castings for the 1903 Wright engine were made at the Buckeye Iron

and Brass Works, a nearby Dayton, Ohio foundry. The engine block and bearing

blocks were aluminum, the rest were cast iron.

Our working replica of the Wright 1903 engine built by Terry Hesler.

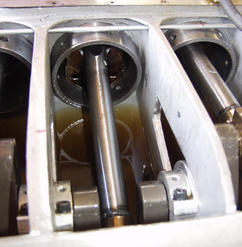

The 1903 Wright engine with the crankcase cover removed.

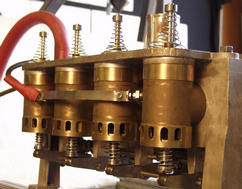

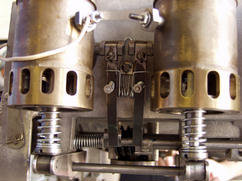

The spark that ignited the gasoline was supplied by a set of

electrical "points" inside each cylinder. The steel arms of the

points tipped with tiny amounts of platinum to forestall corrosion.

As the engine runs, the points momentarily close, making an

electrical connection, and then open again breaking the connection

and creating a spark. This was called a "make-and-break" ignition

system.

The fuel ignition doesn't happen in the cylinders, as in most

internal combustion engines, but in these combustion chambers. The

spring-operated "automatic" intake valves are at the tops of the

chambers, while the cam-operated exhaust valves are at the bottom.

One hundred years of engineering advances separate these two

aircraft engines. The 1903 Wright engine, when coupled to the

propellers, produced 90 pounds of thrust (flb). The most recent

General Electric CF34 Turbofan jet engine generates well over 20,000

flb.

|

The underside of the 1903 Wright engine, showing the oil pump as

well as the cam shaft and rocker arms that operate the exhaust

valves.

1903 engine installed in the Flyer at Kitty Hawk, before it flew. We're

looking at the right side, opposite the pilot.

Charlie Taylor machined most of the parts of the 1903 Wright

engine either from the castings or solid steel. A few, such as the

gears, were farmed out to the Garrison Machinery Works, just a few

blocks from the Wright bicycle shop.

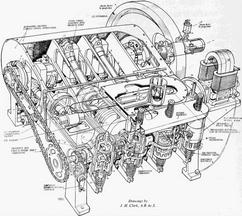

A cutaway drawing of the 1903 engine, showing the assembled parts.

Most of the engine lubrication was "splash-and-dash" -- the

crankshaft churned the oil creating an oily vapor inside the

crankcase. This small oil pump delivered extra lubrication to the

pistons.

A detail showing the mechanism that opens and closes the points.

The 1903 Wight engine had no carburetor to vaporize the fuel.

Instead, gasoline dripped onto the hot engine block through this

opening. As the gasoline evaporated, it was sucked into the

combustion chambers.

A detail showing a piston in its cast-iron cylinder. The cylinder is

mounted in the aluminum engine block. The tube above the cylinder

drips oil onto the interior surface of the cylinder where it is

picked up and distributed by the piston rings.

|