|

Up

Up

KathArinE

KathArinE

Wright

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

atharine

Wright was born at the Wright home at 7 Hawthorn Street, Dayton, Ohio on August 19, 1874 -- her brother

Orville's third birthday. She was the youngest of the offspring of Milton

and Susan Wright, and the only girl to survive. (Her only sister Ida died

in infancy.) Like all the Wright children, she had no middle name -- her

father claimed that he gave his offspring distinctive first names so they

wouldn't need middle names. This may be the reason for the unusual spelling

of her name. Her brothers called her by the nickname "Swes,"

an affectionate German diminutive for "little sister." Most of

her friends called her "Kate." atharine

Wright was born at the Wright home at 7 Hawthorn Street, Dayton, Ohio on August 19, 1874 -- her brother

Orville's third birthday. She was the youngest of the offspring of Milton

and Susan Wright, and the only girl to survive. (Her only sister Ida died

in infancy.) Like all the Wright children, she had no middle name -- her

father claimed that he gave his offspring distinctive first names so they

wouldn't need middle names. This may be the reason for the unusual spelling

of her name. Her brothers called her by the nickname "Swes,"

an affectionate German diminutive for "little sister." Most of

her friends called her "Kate."

Woman of the House

Katharine lost her mother to tuberculosis when she was just

a month shy of 15 years old, and the loss devastated her. Milton sensed

that his daughter's grief was especially deep. Never one to council

inaction, he suggested that she might work through her grief by making a

personal memorial to her mother. Her mother had died in mid-summer, and

Katharine began to collect as many different types of flowers and blooms

as she could find in 1889. These she pressed into an album that she

kept with her always.

With her mother gone, Katharine also

inherited new responsibilities. Her father was a bishop and an important leader in the

Church of the United Brethren, and the loss of his wife was a severe blow

not only emotionally but professionally. He was expected to travel a great

deal -- at one point in his career, he was bishop over all the

congregations of Brethren west of the Mississippi River and east of the

Rocky Mountains. When he was

traveling, he relied on his wife to run the household. When he was home,

he entertained church elders, visiting ministers, and other professional

acquaintances constantly. He needed her help; more to the point, he

expected it. Milton had a commanding presence whether he was home or

away. So fifteen-year-old Katharine

stepped into the role of hostess and head of the Wright household.

The three youngest Wright children,

Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine, were especially close. Some biographers

speculate

that at some point in their

youth Will, Orv, and Kate made a pact never to

marry and always stay together. More likely, they simply preferred each

others' company while they were growing up. But once she reached

womanhood, Katharine apparently had her share of gentleman suitors and

admirers. One of aviators whom the Wright brothers taught to fly once

described her as having "coal black hair, deep blue eyes, and a smile

that could blind you." She was very outgoing and comfortable engaging

anyone in conversation, in contrast to her shy and sometimes withdrawn

brothers. Nonetheless, she remained unmarried until she was well into

her fifties, most likely because she felt a sense of duty to her family,

in particular, her father. In that day and age, it was common among

families for one of the younger siblings to remain at home and take care

of their aging parents.

Oberlin

Milton, for his part, apparently felt

that Katharine should have some career training to fall back on when he had

passed on. In 1893 he sent her to college to become a teacher – one of

the few careers available to women in that era. She would become the only one of the Wright

children to earn a college degree.

Katharine attended Oberlin College

in northern Ohio, among the first colleges in the United States to

admit women, and the oldest coeducational college in America. Living

with other women was a life-altering experience for Katharine, who had grown

up in a house full of men. For the first time, she was on an

intimate basis with women her own age and she quickly made several

deep and lasting friendships. One of Katharine's roommates was

Margaret Goodwin, a minister's daughter from Chicago. She was as

exuberant as Katharine and the two became best friends. Kate also

became close to her other roommate Harriet Silliman, as well as Kate

Leonard who lived at home in Oberlin. Kate and Harriet were

much more serious than Katharine and Margaret, but the four seemed

to round each other out and they became a close-knit group.

Katharine's college life wasn't just filled with women, she also

met a few men. Henry J. Haskell, better known as Harry, took his

meals at Katharine's rooming house. Like Margaret, he was the

son of missionaries. Unlike her, he was intensely studious.

Although he was Katharine's same age, he was two years ahead of her

in his studies. He was also a brilliant mathematician, which

Katharine was not. In fact, she required help with her freshman math

courses and Harry tutored her three times a week. They soon became

fast friends.

Despite her troubles with math, Katharine excelled at most of her

studies, in particular Latin and Greek. In the late nineteenth

century, both high school and college courses were divided into

"information" subjects such as history and physics and "training"

subjects such as the classic languages (Latin and Greek) and

mathematics. The educational theory of the day was that training

subjects exercised the mind, helping to develop mental powers and a

refined character that would serve a person well in all other

endeavors. Katharine found herself studying to become a teacher of

classic languages.

It was customary in Oberlin, as at other coed colleges, for the

men and women to pair off during their senior years. Harry Haskell,

for example, proposed to one of Katharine's housemate's, Isabel

Cunningham. Katharine, however, was out of romantic circulation for

much of her senior year – she had become engaged much earlier. In

1896 at the end of her sophomore year a senior classmate, Arthur Cunningham,

had proposed to marry her when she finished her degree. Arthur graduated Oberlin

that spring, went off to

study medicine in nearby Cleveland, and whatever romance there had

been cooled. When Katharine suggested that they give it up in 1898, he

seemed relieved. Afterward, she referred to the affair as "my narrow

escape." Her father, Milton, never knew that she had been engaged.

Katharine graduated from Oberlin in June of 1898

– it had taken five years to complete her

degree. This was partly because she had missed some of her junior

year. In the early fall of 1896 Orville had come down with typhoid

fever and Katharine had stayed home to help nurse him. Once she had

her diploma, she applied

for, but did not get, a teaching position in Dayton's Steele High

School. Her friend Margaret had better luck, landing a

teaching position in Dover, OH. Harry Haskell started as a cub

reporter with the Kansas City Star. But it took a year for Katharine

to secure a position as a substitute teacher. She began her teaching

career in 1899, the same year that her brothers began their aviation

experiments in earnest.

Veni, Vidi, Volavi*

Upon return from Oberlin, Katharine

also resumed her position as head of the

Wright household, although she hired a maid, 14-year-old Carrie Kayler

(later Grumbach), to help with

cooking and cleaning. By all accounts, Katharine was a taskmaster, riding

Carrie hard and none to gentle with Orville and Wilbur. In many

ways, she had grown up to be her father's daughter, commanding and

authoritarian. At the beginning of one school year, Orville asked her for a list of "the first week's victims" among her pupils.

"I like to see someone else catch it besides us," he explained.

Katharine managed to transplant some of the

rich social life she had enjoyed in college to Dayton. Suddenly

there were parties and bicycle outings and camping trips originating

at 7 Hawthorn Street. Occasionally Margaret or Harriet would come to

visit, but for the most part Agnes Osborn, a childhood friend, was

Katharine's comrade-in-arms for these events. Orville, too, seemed

drawn to these gatherings despite his legendary shyness. He often

appears in photos of the parties, against a wall or off to one side,

looking dapper but slightly out of place. He even courted Agnes Osborn and may have proposed marriage, but

nothing came of it.

By 1901, Katharine was teaching full time at Steele High School.

Her first assignment was to teach beginning Latin. Because this was

a required course for all the students, Katharine was saddled with

poor students as well as good – including some who were

outright disruptive. Fortunately, as the only sister of four older

brothers, she was no stranger to boisterous behavior. That coupled

with her self-assurance and natural bossiness made her more than a

match for teenage boys. "I had five or

six notoriously bad boys assigned to my room," she wrote to her

father. "I was ready for them and nipped their smartness in the

bud."

As her own career developed, she watched her brothers evolving

work on the problem of manned flight with a mixture of interest,

annoyance, humor, encouragement, and admiration. When Octave

Chanute, renowned engineer and world authority on aeronautics,

visited the brothers in June 1901, Katharine played hostess. When

Chanute invited Wilbur to speak on his aviation experiments before

the Western Society of Engineers and Wilbur waivered, Katharine

convinced him to go. "Will was about to refuse but I nagged him into

going," she wrote Milton. ""He will get acquainted with some

scientific men and it may do him a lot of good."

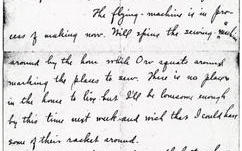

As Will and Orv labored over their breakthrough design, the 1902

Wright Glider, preparing to take it to Kitty Hawk, NC, she complained

and lamented, "The flying machine is in the process of making now.

Will spins the sewing machine around by the hour while Orv squats

around marking the places to sew. There is no place in the house to

live but I'll be lonesome enough by this time next week and wish

that I could have some of their racket around."

When her brothers moved their test flights from Kitty Hawk, NC and

began to perfect their powered flying machine at Huffman

Prairie just outside Dayton, Ohio, Katharine would

round up a few

trusted teachers to

come out and help with the experiments. The aircraft and the launching

mechanism were too large for the Wright brothers to handle on their own.

In the summer of 1904, Katharine traveled to the St. Louis

Exposition in St. Louis, MO with Margaret Goodwin. The massive

exposition marked the centennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

and celebrated the advances that had been made since Captains

Merriweather Lewis and William Clark first explored the newly

purchased territories of the western United States. Kate and her BFF

viewed new wonders of technology, transportation, electricity, and

arts while sampling ethnic foods. They also tasted several new ones invented just

for the occasion, such as the ice cream cone and cotton candy. While

at the fair, Margaret fell ill with severe gastric distress. Later,

doctors diagnosed a tuberculosis-like infection that

had lodged in her intestines. She recovered somewhat in July, but

the illness returned in 1905 and spread to her brain. Margaret died

in the spring of 1906.

Once again Katharine was grief-stricken and again she threw

herself into a project to shake off the grief. Her brothers had

achieved a practical flying machine in 1905 and secured a patent in

1906. Now they were trying to sell their airplane, a task that

proved to be more daunting than inventing it. Katharine joined them

in the attempt, essentially becoming their executive secretary.

It wasn't the first time that Katharine had minded her brothers'

business. During the years that Wilbur and Orville had traveled to

Kitty Hawk, Katharine had watched over the bicycle shop, paying

bills, depositing receipts, and fighting with the help

– she and Charlie Taylor, the Wrights'

machinist, were not fond of one another. With the newspaper reports

of her brothers' flights, as inaccurate as they were, the Wrights

had achieved some notoriety. When the Wrights went to Europe in 1907

to sell their invention abroad, the spotlight on them became

brighter and the responsibilities of Katharine's unofficial position

increased. She answered queries for scientific information,

corresponded with newspapers and magazines trying to keep their

stories straight, screened business offers and politely handled

cranks. When Webster's Dictionary asked to publish a photo of the

Wright Glider, she obtained her brothers' permission for them. All

this she accomplished while continuing to teach at Steele High

School.

The Social Manager

By 1908, Wilbur and Orville had two solid contracts, one with a

consortium of French investors and the other with the United States

Army. Wilbur went to LeMans, France and Orville to Fort Myer near

Washington, DC, each to demonstrate their flying machine. The

initial flights had gone extremely well for both brothers and

Katharine begged them for details of their success. Back in Dayton,

things were not well. Katharine was helping to nurse her nephew –

Lorin's son Milton – through typhoid fever. At the same time, the

superintendent of Dayton's schools had decided he could save money

by reducing the salaries of his female teachers.

Thankfully, young Milton recovered from the typhoid. But just as

he was back on his feet, word came from Fort Myer that Orville had

been in an accident, breaking his leg and several ribs. Within two

hours of getting the news, Katharine was on a train for Washington,

leaving her classes to a substitute teacher. Arriving the next

afternoon, she found the accident had been worse than she feared. In

addition to the broken bones, Orville had concussed his spinal chord

and had severe scalp wounds. His passenger, Lt. Thomas Selfridge of

the US Army, had died. Katharine immediately set up a routine to

help nurse Orville and take care of the airplane business. For the

next six weeks, she was at his side most of the day, talking to

doctors, answering mail, receiving visitors, even helping to

investigate the accident. She left around dawn to get some breakfast

and a few hours sleep, then was back in the hospital by afternoon.

By Late October, Orville was well enough to return home to Dayton. Once

there, Wilbur, who himself had been worried sick about Orville, sent an

invitation to both Orville and Katharine to come to Europe. Katharine

responded that Wilbur should come home. But Wilbur repeated his

invitation in December and sweetened it with this offer: "We will be

needing a social manager and can pay enough salary to make the

proposition attractive, so do not worry about the six per day the school

board gives you for peripateting about Old Steele's classic halls."

Katharine requested that the school board extend her leave of absence

until the next school year and in January of 1909 she and Orville

boarded an ocean liner bound for France.

Wilbur had left LeMans and relocated his flying demonstrations in

Pau, a city in southern France where the weather was warmer.

Katharine dived into her new job and immediately began to manage her

brothers' social calendar. She spent two hours every morning

learning French, emerged for a lunch meeting with business prospects

and contacts, then went to the flying field to meet with the

aristocracy and the rich who had come to see her brother fly.

Neither Wilbur nor Orville, because they were so shy, were

especially good at schmoozing the people who could buy their airplanes.

Katharine, however,

provided the social chemistry the Wrights needed to make their enterprise

work and she soon had the Europeans eating out of her hands. Once,

when preparing to meet the king of Spain, she practiced the proper

curtsey with the wife of an English baronet. But when King Alfonso

XIII showed, she forgot herself and greeted him American-style with

a simple handshake and a brilliant smile. The king was won over.

Katharine made her first flights while in Europe

– she was the third woman to fly in an

airplane, behind

Teresa Peltier and

Edith Berg. Wilbur took her aloft several times, once in front

of King Edward VII of England ostensibly to make the point that even

young ladies could travel through the air as easily as in motorcars.

"Them is fine," Katharine wrote to her father Milton after her first

flight. It was an old family expression meant to convey that the

experience was as good as it could possibly get. She was also

treated to a balloon flight by the Marquis Edgard de Kergariou, a

French politician and accomplished aeronaut.

With Katharine so much in the spotlight,

journalists began to speculate on her role in the development of the

airplane. Rumors spread that she sewed the wings, loaned her

brothers money, even did the complex mathematics they required to

design their aircraft. None of it was true,

but

the speculation and the interest showed just how important the Europeans thought she was to their

efforts. When the Wrights left France, the French awarded all three of

them – Katharine included – the

Ordre national de la Légion

d'honneur (Legion of Honor). She remains one of the

few American women to have received this award.

Fame followed Katharine back to

America. Both she and her father Milton had places of honor in

Dayton's homecoming celebration. She was invited to Washington, DC

for a special reception with President Taft and presentation of

medals at the White House. While in the Capital, she ran across an

old friend from Oberlin. Harry Haskell was working the Washington

beat for the Kansas City Star and he had asked to interview

Orville and Wilbur. He was granted the interview, but spent a good

deal more time catching up with Katharine.

All three Wrights were back in Washington just

a few weeks later with a new airplane so that Orville could continue

the US Army trials that had been interrupted the previous year. They

concluded easily and the Army purchased its first aircraft.

Katharine returned to Dayton ready to resume teaching, but her

services as a social manager were needed once again. A German

concern wanted to license and produce Wright Flyers. Orville was

called back to Europe to demonstrate the airplane and

Katharine was needed to handle everything else. Realizing that

Steele High School couldn't keep her position open forever, she

resigned as teacher.

A Change of Focus

While she was in Germany, a group of American

investors came together to underwrite the Wright Company, a

corporation for the manufacture, demonstration, and sale of of

Wright aircraft. With the incorporation, there was no longer any

formal place for Katharine in the airplane business. Instead, she

found herself doing volunteer work. She became the director of the

Young Women's League of Dayton and an active supporter of women's

right to vote. She also took charge of the design and construction

of

Hawthorn Hill, the new Wright home in Oakwood, just south of

Dayton.

In early May of 1912, Wilbur came home from

Boston not feeling well. His illness soon progressed to

typhoid fever and hung on for nearly a month. Wilbur would rouse

briefly only to sink again, each time a little lower. He died on May

30 and his death stunned both Katharine and Orville, perhaps more so

than the death of their mother. Both of them blamed his death on

overwork; Wilbur had been wrung out by constant court battles to

protect the Wright patent.

Orville stepped into the role of president of

the Wright Company and Katharine became its secretary.

If you bought a share of stock in the

company during this period, it was signed by both Orville

and Katharine. But Orville wasn't executive material and missed Wilbur far

too deeply to be comfortable with the position. Then in 1914 the

focus of his life suddenly changed. Glenn Curtiss, the target of

much of the Wrights' patent litigation, "restored" and flew the 1903

Langely Aerodrome. Samuel Langley, the deceased director of the

Smithsonian Institute had tried and failed to fly this machine just

before Orville and Wilbur's first successful flights at Kitty Hawk.

Curtiss flew it to prove that the Wright Flyer was not the beginning

of powered aviation. The Smithsonian began to display it as the

"first aeroplane capable of flight," ignoring the fact that Curtiss

had made over 30 major changes to the Aerodrome to make it

airworthy.

Orville and Katharine were incensed

beyond measure. Orville sold

the Wright Company in 1915 and built a small research laboratory not

far from the site of the Wrights' bicycle shop. He continued to do

research and consult in aviation, but

his life goal became to expose

the Smithsonian's lies and preserve the recognition he and his

brother had earned as the creators of the first practical airplane.

Katharine became Orville's partner in this struggle as well as the

mistress of their new home at Hawthorn Hill.

The Wrights also acquired a summer home. In

1916, Orville took his sister and father on their first family

vacation ever. They stayed at a cottage on Georgian Bay in Lake

Huron and Orville fell in love with the rough landscape. In many

ways, it was like Kitty Hawk, completely devoid of modern

conveniences and unwanted interruptions. Before they returned home,

Orville had purchased a 20-acre island with a few primitive

buildings. Thereafter,

Orville and Katharine spent two months of

every year on Lambert Island, enjoying the wildness.

In 1917, Milton died. His death was the end of

a long, slow decline so it was not a surprise to Katharine or

Orville. But for some reason Milton's departure left an emotional

vacancy that the two remaining Wrights decided to fill with a puppy.

Orville bought a St. Bernard pup from Nina Dodd’s White Star

Kennels in Long Branch, New Jersey for $75 and had him shipped to

Dayton. Katharine named him "Scipio" after the famous Roman general

that had defeated Hannibal and thwarted an invasion of Rome. The dog

was much loved. When Orville died 15 years after Scipio had passed,

there were still photos of the St. Bernard in his wallet.

Marriage and Beyond

Not long after Scipio arrived, Katharine slowly began to fill

another emotional vacancy -- so slowly that she was unaware of it

for several years. Since they had renewed their friendship in 1909,

she and Harry Haskell had exchanged occasional letters. Their

contact increased when Orville and Katharine began their feud with

the Smithsonian and Harry supported them with editorials in the

Kansas City Star. Then it increased again when both Harry and

Katharine were invited to join the board of trustees for Oberlin

College.

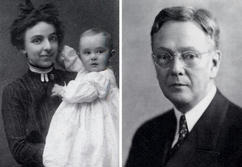

In 1923, Harry's wife Isabella died of cancer. Katharine began to

write him often, consoling him as he poured out his grief to her.

Slowly, grief gave way to affection, then to love. Harry was the

first to realize where this was going and declared his feelings to

Katharine in a letter in June 1925. Katharine was at first confused,

then excited as she realized she also loved Harry, then frightened

when she realized what this would mean to her comfortable life with

Orville. Harry was cool; he did not press her. He dropped by Dayton

for a face-to-face meeting; they admitted their mutual feelings; but

Harry was considerate of her concern for Orville. They arranged

another meeting – Katharine invited Harry

to visit Lambert Island. Harry arrived during the last week of July

and they finally kissed while Orville was out fishing. By the time

Harry left on August 11, they had decided to get married. Orville

was completely clueless as to what was going on between Katharine

and Harry. Katharine decided it would be best if she told Orville,

but she couldn't bring herself to do it for more than half a year.

Finally, she gave the task back to Harry. He informed Orville during

a visit to Hawthorn Hill in May 1926. Orville sat silent, saying

nothing. When Harry left the next day, Orville descended into a

world-class sulk. Katharine despaired, afraid that her family

would condemn her for wanting to leave Orville. But when she told

her brother Lorin and his wife Netta, they were thrilled. So was

Reusch's widow, Lulu. Lorin tried to reconcile Orville to what was

really a happy occasion for the family, but Orville would have none

of it. He was dependent on Katharine.

She provided his social interface with the world. Without her, he

would have to deal with people directly. Even after all the

acclamation he had received as co-inventor of the airplane, he was

so painfully shy that this was unthinkable for him. Besides that,

she was his best friend. He began to act as if she were dead. In

point of fact, although there was no sexual relationship

between Orville and his sister, he behaved as if she had been

unfaithful.

Katharine Wright married Harry Haskell on November 20, 1926 in

Oberlin. From the wedding she traveled directly to Kansas City. She

never saw Hawthorne Hill again, although she remained in contact

with Carrie and always knew how Orville was doing without her. And

despite Orville's painfully selfish reaction, she was extremely

happy with her new life. Harry's family welcomed her, particularly

his son Henry to whom Katharine grew especially close. Good things

happened, at least for a short while. The Kansas City Star

was sold to its employees and Harry became a major stockholder as

well as an officer in the publishing firm. More important, Harry's

professional reputation as an editorial writer grew daily. The paper

won a Pulitzer Prize for its editorials in 1933 largely due to his

efforts, and Harry was awarded his own Pulitzer for editorial

writing in 1944.

Harry and Katharine decided to take a voyage to Italy and Greece

in 1929 – they both shared a love of these

classic cultures and languages, the result of their Oberlin

education. But it never came off. Just before they were due to board

the ship, Katharine came down with pneumonia and began to sink

quickly. Lorin arrived from Dayton, then called Orville, told him to

dig himself out of his funk and get on a train to Kansas City.

Orville arrived on March 2, a day before Katharine died. Harry

escorted Orville to Katharine's room and announced, "Here is Orv,

Katharine. Do you recognize him?"

"Yes, of course," Katharine whispered.

Katharine Wright Haskell is buried in

Woodland Cemetery

in Dayton, Ohio, with her

mother, father, Wilbur, and Orville. In the 1930s, Harry gave a

bequest to Oberlin College to construct an exact copy of of the Fountain of

Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, a sculpture he and

Katharine might have seen had they made it to Italy. Atop the

fountain is a winged cherub playfully clutching a fish.

Unless you know something of

classical art – and Harry Haskell knew plenty – it's not

immediately clear why Harry chose this particular statue as a

tribute to Katharine. What appears to be a cherub is actually a "putto,"

the mythological Greek being associated with Cupid and love. The

fish is a dolphin, the "helios

ichthus," a favorite of Apollo, god of wisdom, whom he sent to

guide sailors. And there you have it – love and wisdom.

The replicated fountain now sits in front of Oberlin's

Allen Memorial Art Museum with this simple inscription: "To Katharine Wright Haskell

1874–1929."

It was recently restored in 2007.

*For those not versed in Latin, "Veni,

Vidi, Volavi" means "I came, I saw, I flew." This is a paraphrase

of a famous line from Julius Caesar. When asked by the Roman Senate

to report on his Persian campaign, he said simply, "Veni, vidi, vici" – "I came, I saw, I conquered."

Katharine would have covered this in her Latin classes. |

Katharine Wright in 1875, age 1 year.

Katharine in 1879 at age 5, just before

entering elementary school

Katharine and her fifth grade class in 1884.

Katharine is in the first row, second from the right.

Oberlin College at the turn of the twentieth

century.

A bicycle outing in Oberlin. Katharine is in the front row wearing a

coat.

Harry Haskell (right) being his studious self in Oberlin.

Arthur Cunningham was also a football

player for Oberlin College. He's in the middle row, second from the

left.

Katharine's portrait upon graduating from Oberlin in 1898.

Steele High School in Dayton, Ohio in 1899. It was on Monument Street,

overlooking the Great Miami River.

Katharine doing the dishes at 7 Hawthorne Street about 1900.

A party at 7 Hawthorn Street. Katharine in

right-most on the front row, talking with her friends. Orville

is left-most looking ill at ease.

A camping trip, north of Dayton, in 1899. Katharine is sleeping while

her friend Harriet Silliman reads. Orville, who was along for the trip,

is probably taking the photo. While this outing was in progress,

Wilbur

conducted his famous kite experiment back in Dayton, rolling the kite in

the air by warping its wings.

A letter from Katharine to Milton, describing the progress of the 1902

Wright Glider.

Orville (right) about to take off from Fort Myer with Lt. Thomas

Selfridge (left).

The aftermath of the crash in which Orville was injured and Lt.

Selfridge killed.

Katharine charms Lord Northcliffe (left), a British newspaper magnate.

Katharine watching Wilbur Fly in Pau.

Katharine ready to take off with Wilbur in Pau. Orville is on the left.

Note the string around Katharine's skirt.

Upon leaving France, the French awarded Katharine

and her brothers the

Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur.

Katharine stands out in a white dress with her brothers and President

Taft (center) at the White House.

Katharine, Orville, and a passenger on their way to Germany in 1910.

Harry Haskell (right) a few years before he met Katharine in Washington

DC. On the left is his wife Isabella and son Henry.

Hawthorne Hill in 1914 just after the Wrights moved in.

Katharine about to take a ride with Orville in a Wright Model H in 1915.

Katharine and Scipio on Lambert Island about 1920. To visit Lambert

Island on Google Earth,

CLICK HERE.

Katharine christens a flying boat, the

Wilbur Wright, in 1922. The aircraft had been designed by Grover

Loening, an engineer that once worked for the Wright Company.

Harry Haskell visiting Hawthorn Hill in 1924.

Harry and Katharine Haskell's home in Kansas City.

Katharine's fountain at Oberlin College when it was completed in 1933.

To visit the fountain on Google Earth,

CLICK HERE. To visit the original Fountain of Palazzo Vecchio in

Florence, Italy,

CLICK HERE.

|