|

Up

Up

A Long Twilight

A Long Twilight

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Restored

Personal Spaces

Back in Business

NACA

Old Flames

A Safer Gentler

Airplane

All in Good Fun

Exiled

Streamlining

Monumental

Achievements

Mission

Impassable

The Edison Institute

Cipher

At Peace

The Last

Airplane

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

rville

Wright’s life changed dramatically in 1914. The year had started on

a high note. On 13 January 1914, the United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit judged the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to

have infringed on Patent No. 821,393 – the Wright brothers’ 1906

patent on an aircraft control system. At the same time, Chief Judge

Learned Hand upheld a previous decision by Judge John R. Hazel,

declaring the patent was entitled to “liberal interpretation” and

designating it as the grandfather or “pioneer” patent of the

aviation industry. This had happened only a handful of times in the

past, most notably when Alexander Graham Bell had his telephone patent

adjudicated to be the pioneer patent of the telecommunications

industry. rville

Wright’s life changed dramatically in 1914. The year had started on

a high note. On 13 January 1914, the United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit judged the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to

have infringed on Patent No. 821,393 – the Wright brothers’ 1906

patent on an aircraft control system. At the same time, Chief Judge

Learned Hand upheld a previous decision by Judge John R. Hazel,

declaring the patent was entitled to “liberal interpretation” and

designating it as the grandfather or “pioneer” patent of the

aviation industry. This had happened only a handful of times in the

past, most notably when Alexander Graham Bell had his telephone patent

adjudicated to be the pioneer patent of the telecommunications

industry.

But the victory was fleeting. Glenn Curtiss

responded by convincing the Smithsonian Institution to let him

borrow the remains of the 1903 Langley Aerodrome A and try to

fly it. The Smithsonian, for its part was also anxious to see

Langley's airplane fly;

the failure of the 1903 test flights had haunted the Smithsonian and

diminished it politically. Beginning in May, Curtiss made a series of brief

hop-flights in

a much-modified and improved Aerodrome. In its annual report,

the Smithsonian ignored the modifications and claimed, “…former

Secretary Langely had succeeded in building the first aeroplane

capable of sustained free flight with a man.” The Curtiss lawyers

prepared to argue that since the Aerodrome A was flightworthy

and could have flown before the Wright Flyer, the Wright brothers’ work was not the foundation of

aviation. The Smithsonian claimed Samuel Langley was vindicated and

displayed the rebuilt Aerodrome A as the “the

first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of

sustained free flight,” essentially rewriting aviation

history.

Orville was outraged and determined to protect

his and his deceased brother’s reputation. He sold his company,

ridding himself of the day-to-day responsibilities of management,

and launched himself into a battle to convince the Smithsonian to admit

that (1) Curtiss had made dozens of modifications to the Great

Aerodrome, (2) without these modifications, the Aerodrome

was incapable of flight, and (3) the 1903 Wright Flyer was

the first to make a “sustained, controlled, powered flight” with a

man aboard..

At the same time, he continued to contribute to

aviation and several other industries. Most biographies portray him

as a “tinkerer” during this period, recalling family stories of his

attempts to invent a record changer or his contrived “railroad” that

ferried groceries to his vacation home on Lambert Island. Nothing

could be further from the truth. A little over a year after he sold

the Wright Company, he joined another venture in which he

participated in the design of the first guided missile and

participated in the development of the legendary Liberty

engine. He designed a record-setting cabin biplane, the OW-1. He was a lifelong member of the board of directors of NACA

(later NASA), and also served on the board of the Guggenheim Fund,

helping to develop instrument flying and improving flight safety. He

worked on aerodynamic bodies for automobiles, the electromechanical

works of what would become the first computers, even designed toys and

improved means of toy manufacture. Perhaps the reason that history

overlooks these accomplishments is the Orville thoroughly enjoyed

being part of a team, just as he had once teamed with Wilbur. And

more often than not his shy nature kept him in the background letting others enjoy

the spotlight.

Besides, none of these endeavors, however

exciting or important, warranted his complete and enduring focus –

none except his private war with the Smithsonian.

Timeline:

-

1916 – For the first time since

1903, Orville opens the boxes containing the parts of 1903

Flyer. He restores the aircraft for its first public showing at

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He will show it

several more times at special events over the next decade. This

relic will become his most potent weapon in his struggle with

the Smithsonian.

-

1916 on – Since his family moved to

Hawthorne Hill in 1913, Orville had taken on the care of the

mansion and adapted it to be his machine for living. Now he

built two more personal spaces. Leaving his offices at the

Wright Company, he built a small personal office and laboratory

at 15 North Broadway in Dayton, Ohio, just a few blocks from his

former home. That same year during a vacation in Canada, Orville

purchased Lambert Island in Lake Huron to be his summer home,

and immediately began rearranging and rebuilding the structures

on the island to suit himself. Both Hawthorne Hill and Lambert

Island took on a new importance to the Wright family when Bishop

Milton Wright died in 1917 and Orville became its new patriarch.

-

1917 to 1923 – Orville lends his

name to the newly incorporated Dayton Wright Aeroplane Company

(later Dayton Wright Aeronautical Corporation). He also accepts

a position as consulting engineer. In this capacity, he

participates in the development of aircraft engines, a guided

missile, a cabin biplane, wing shapes, retractable landing gear, and many other

improvements in aircraft design. Additionally, he frequently

consults at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio where the Army Air

Corps has set up its central research and design facility.

-

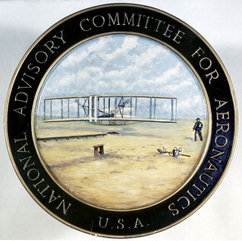

1920 – The National Advisory Council

on Aeronautics (NACA) had begun quietly in 1915 at the prompting

of the Smithsonian and other scientific institutions. It’s original purpose was to help direct and

coordinate the aeronautical research and manufacturing programs

in the United States, but its mission quickly grew to include

research in advance aviation technology. In 1917, NACA built its

first research laboratory near Norfolk, Virginia. By 1920, it

employed over 100 scientists and President Woodrow Wilson

appointed Orville to its board of directors. Orville would serve for

28 years, until his death.

-

1922 to 1929 -- Katharine Wright

begins to correspond with an old friend from Oberlin College,

Henry J. Haskell, now editor and part owner of the Kansas

City Star newspaper. In 1924, Katharine is appointed to the

board of directors of Oberlin College along with Haskell and the

two begin to see more of each other. In 1926, she announces her

engagement to Henry. Orville is distraught, convinced she has

violated a pact between them. He refuses to attend her wedding

on 20 November 1926, and then ignores Katharine and her new

husband when the couple moves to Kansas City. Two years after her wedding, Katharine

contracts pneumonia. Orville’s brother Lorin convinces Orville

to see her. He arrives at her bedside just before her death on 3

March 1929.

-

1923 to 1930 – At the request of his

niece Ivonette, Orville designs Flips and Flops, a toy

catapult that launches a miniature clown. If launched just

right, the clown catches a trapeze and whirls around. The toy is

manufactured by the Miami Wood Specialty Company, in which

Ivonette’s husband has invested. Later on, when brother Lorin (Ivonette’s

father) buys into the company, Orville designs a printing press

that will print on balsa wood, adding color and graphics to toy

airplanes.

-

1925 to 1930 -- Orville joins the

board of directors at the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the

Promotion of Aeronautics. The Guggenheims were concerned that the United States was falling behind in aviation

and organized the fund to bring it up to speed. They helped

establish new aeronautical engineering programs at universities,

and sponsored programs to develop aerial navigation,

instrument flying, and flight safety. The fund disbanded in 1930

having accomplished its purpose, but the Guggenheim foundation

continued to sponsor advanced research in aeronautics and

established the Guggenheim Medal for exceptional contributions

to aviation. The first medal, award in 1930, went to Orville

Wright.

-

1925 to 1928 – After several

reports and articles appear supporting the Smithsonian’s position

that the Langley Aerodrome was the first aircraft “capable” of

flight; Orville Wright announces that he will send the 1903

Wright Flyer to the Science Museum in Kensington, England.

Here he says the curators will give his deceased brother Wilbur

and himself the credit they deserve as the inventors of the

airplane. The decision causes uproar in press. Smithsonian

Secretary Charles Abbot issues paper that partially recants the

Smithsonian’s position. Abbot also reduces the label on the

Aerodrome A display to read simply, “The Original Langley

Flying Machine of 1903, restored.” It is not enough for Orville;

he wants the Smithsonian to address the 1914 Aerodrome

test-flights and admit that these did not prove the Aerodrome

could have flown in 1903.

Abbot balks and Orville sends the Flyer off to Kensington in 1928.

-

1927 to 1934 – Carl Beer, chief

engineer of the Chrysler Company, engages Orville Wright to help

design and oversee wind tunnel tests to create an aerodynamic

automobile. The result, introduced in 1934, is the DeSoto

Airflow, which eventually breaks 32 stock car records, including

the fastest mile at 86.2 mph.

-

1926 to 1940 – The first monument

erected to the Wright brothers was a simple granite obelisk

commissioned by their old “banker” friend Captain William Tate

and placed in his front yard in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Dedicated in 1927, it marked the spot where Wilbur had built the

1900 glider and where, Tate insisted, the Age of Aviation began.

This was followed in 1932 by a mammoth granite shaft carved with

Art Deco wings atop the “Big Hill” at Kill Devil Hills.

Conceived by North Carolina congressman Lindsay Warren and U.S.

Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut, its

purpose – besides commemorating the Wright brothers – was to

attract tourists to the Outer Banks. And it did. Dayton, Ohio

finally got its own monument in 1940, yet another granite shaft

on a ridge overlooking Huffman Prairie.

-

1933 to 1937 – At the suggestion of

Secretary Charles Abbot, Charles Lindbergh heads an attempt to

reconcile the differences between the Smithsonian and Orville

Wright. All three men meet and Orville makes his case very clear:

Admit that the 1903 Langley Aerodrome had been

extensively modified before its 1914 test flights and retract

the report that declared the Aerodrome was the first

airplane capable of flight. Abbot makes two counterproposals,

first that the issue be decided by a committee of government

officials; and then, when Orville rejects this, that the

Smithsonian prepare a paper

describing a complete history of the controversy, including

Langley’s work in aeronautics, the history of the Aerodrome, the

Smithsonian's 1914 report, Orville’s list of changes, the

Smithsonian’s notes on Orville’s list, and all that had happened

since 1914. Orville objects; this is too complex; it obscures

the heart of the controversy. Abbott objects to publishing

Orville’s list without context. Lindbergh eventually gives up.

In

preparing his will, Orville states that unless the will was amended

by a letter from him, the 1903 Flyer should remain in

England.

-

1936 to 1938 – Edward Scripps,

president of an influential organization of pioneer aviators

known as the Early Birds, approaches Orville about moving the

Webbert Building – once the Wright Cycle Shop – to Dearborn,

Michigan where Henry Ford is building an educational facility

and museum to honor American inventors. It’s called the Edison

Institute and will later be known as Greenfield Village. Orville

views this as a positive development in his ongoing feud with

the Smithsonian. His old shop will be enshrined in a major

American museum as the place where he and his brother invented

the airplane. Orville agrees with the caveat that the Early

Birds agree to recognize Orville and Wilbur Wright as the first

to fly and support Orville’s claim against the Smithsonian. When

Henry Ford comes to Dayton to arrange the transport of the bike

shop, he discovers the old Wright home at 7 Hawthorne Street is

available and buys it as well. The shop and home are moved to

Michigan and opened to the public in 1938.

-

1942 to 1945 – Beginning in 1926,

the German Navy depended on the Enigma cipher machine to code

and decode sensitive communications. This machine featured a

series of rotors that could be set in thousands of different

combination to create a new code each time it was used. The

British “Ultra” team cracked the code with primitive computers

in 1940, but the Germans added more rotors and once again made

the code undecipherable. In 1942, the National Cash Register Company,

under the direction of Joseph Desch, built a 7-foot-high,

11-foot-long, 5000-pound electromechanical computer called a

“bombe” that cracked the German code once and for all.

Orville Wright was among the many Dayton scientists who

contributed to this secret program. His focus seems to have been

the development of a better code machine for the Allied Forces.

-

1939 to 1948 – Fred C. Kelly, while

writing a biography of the Wright brothers, contacts Smithsonian

Secretary Charles Abbott and volunteers to take one more crack

at resolving the feud. Kelly learns from Orville just what is

needed for reconciliation – a list of the differences between

the 1903 and 1914 versions of the Aerodrome and an admission

that the 1914 report on the test flights was inaccurate. Kelly guides Abbott’s hand in

writing this resolution, Orville accepts it, and both

Orville and Abbott agree to announce the resolution in the 1942

Smithsonian Annual Report (due to be published in the summer of

1943). However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asks to be

allowed to make the announcement during a special dinner at the

White House on December 17, 193 -- the fortieth anniversary of

the first flight at Kitty Hawk. Just before the dinner, Orville

writes to the

curators of the Kensington Science Museum and asks for

the return of the Flyer. Unfortunately, there is a war

on and the Flyer was stored in a British quarry for safekeeping.

The Science Museum also asks for time to build an exact copy of

the Flyer after the war is over, and Orville agrees. The Flyer

is not returned until 1948, the year Orville

dies.

-

1946 to 1950 – Dayton industrialist

Edward Deeds determines to build a historical park in Dayton and

asks Orville to contribute an airplane. Orville suggests the 1905

Wright Flyer III, which he and his brother Wilbur had

considered the world’s first practical airplane. The Flyer III

had been abandoned in Kitty Hawk in 1908, but it was salvaged in

1911. Orville acquired the remaining pieces and worked with

Harvey Geyer (a

former employee of the Wright Company) and Louis P. Christman

(an employee of National Cash Register) to restore

it. Orville did not live to see the Flyer III restored –

he died of a heart attack on 30 January 1948. But the Flyer

III was completed and unveiled at Carillon Park in Dayton,

Ohio in June of 1950. Because was the final result of the

seven years of experimentation that led to the invention of the

airplane, many historians have called it aviation’s most

valuable artifact.

Note: You may also want to consult the

Wright Timeline.

|

The 1903 Wright Flyer on display at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology (MIT) in 1916.

Orville with his dog Scipio at Lambert Island in

Georgian Bay, Lake Huron, Ontario, Canada.

Although the De Havilland DH4 produced by the Dayton Wright

Aeroplane Company was a British design, it was powered by the

Liberty engine designed in Dayton, Ohio.

The NACA seal shows the Wright Brothers first flight in 1903.

The Miami Wood Specialty Company produced Orville's design for the

"Flips and Flops" toy for several years.

Orville (lower left) with several members of the Guggenheim Fund

board, including Charles Lindbergh (top left).

"Wrong Way" Corrigan, an American pilot who flew across

the Atlantic Ocean not long after Lindbergh, inspects the 1903 Wright Flyer hanging in the

Kensington Science Museum.

Orville assisted in the wind tunnel tests that resulted in the first

aerodynamic car design, the Desoto Airflow.

Orville Wright was one of the few Americans to have a national

memorial erected to him while he was still alive.

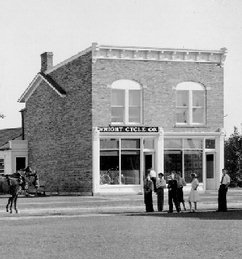

The Wright Cycle Shop, formerly of 1127 West Third Street in Dayton,

Ohio, now at Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

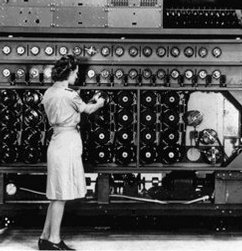

The code-busting "bombe" developed at National Cash Register in

1943.

The prototype code machine that Orville Wright developed during

World War II looked to be a simple affair, but it could generate

over 11 million codes. Had it been put into use, these codes would

likely have been indecipherable to the NCR bombe and other primitive

computers of the day.

The 1903 Flyer being unloaded from the USS Palau after its trip

across the Atlantic in 1948.

The restored 1905 Wright Flyer III at Carillon Park in Dayton, Ohio.

|