|

Up

Up

Kitty Hawk

Kitty Hawk

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

s

Wilbur and Orville labored over the design of their first glider in

the autumn

of 1899, they faced three major engineering tasks. First the wings had to generate

enough lift to support the weight of the glider and the pilot. For

this, they relied on the formulas and tables of data that

Lilienthal had

gathered during his lifetime. Will calculated that a biplane with a 20-foot

(6 meter) wingspan and a 5-foot (1.5 meter) chord – slightly larger

than

Chanute's glider – would do. He

planned a much flatter wing camber (curved shape) than Lilienthal,

however. Lilienthal had used a 1:12 camber – the wing curve was

1 inch high for ever 12 inches wide. Wilbur's kite experiments

likely taught him that wings with deep cambers were harder to

control than those with shallower curves. His camber would be just 1:20. s

Wilbur and Orville labored over the design of their first glider in

the autumn

of 1899, they faced three major engineering tasks. First the wings had to generate

enough lift to support the weight of the glider and the pilot. For

this, they relied on the formulas and tables of data that

Lilienthal had

gathered during his lifetime. Will calculated that a biplane with a 20-foot

(6 meter) wingspan and a 5-foot (1.5 meter) chord – slightly larger

than

Chanute's glider – would do. He

planned a much flatter wing camber (curved shape) than Lilienthal,

however. Lilienthal had used a 1:12 camber – the wing curve was

1 inch high for ever 12 inches wide. Wilbur's kite experiments

likely taught him that wings with deep cambers were harder to

control than those with shallower curves. His camber would be just 1:20.

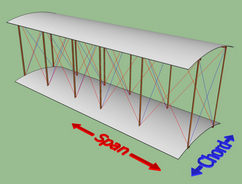

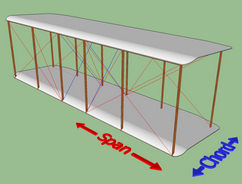

Second, the wings had to be flexible so the

brothers could twist them. Chanute's glider had been completely

rigid along its span (wing tip to wing tip) and chord

(leading edge to trailing edge). The Wrights decided to brace their

machine along its span, but to only brace the chord of the middle

bay, where the pilot lay. This would allow them to twist the wings

along most of their length.

Finally, they had to add a control system –

a means for the pilot to move the aerodynamic control surfaces that

they hoped would balance and navigate the glider in the air. To

twist the wings, they ran cables from the wing tips to a kickbar

that they operated with their feet. They placed a horizontal elevator in front of the wings

(a

configuration that would later be called a canard) and simply lifted

or depressed the back edge with their hands. The completed aircraft

looked a lot like a Chanute-Herring glider with the tail in front.

Tail First

Tail First

Rudderless

There was no rudder. In the time they had spent watching birds,

the Wrights had seen no evidence that a rudder was necessary to fly.

Birds had wings which they twisted to roll themselves right and

left, and and a flat horizontal tail that they used to pitch

themselves up and down. At this point in their experiments, the

brothers were convinced that all they needed to

navigate in the air was wing warping to turn and an elevator to adjust

altitude. They had missed something important, but would not

discover their mistake until they had some actual flying experience.

Although they opted to place their elevator in front of

wings, they did not completely dispense with the tail. Even

though they no longer planned to use it as a control surface, they

attached a tail to the back of the glider for stability -- and insurance.

Wilbur wrote to his father, "The tail of my machine is fixed and even

if the steering arrangement should fail, it would still leave me with the

same control that Lillienthal had at best." Wilbur thought that if

the horizontal elevator and the wing warping were not enough to balance

the glider in the air, he could revert to shifting his weight as

Lillienthal and Chanute had done.

Wind and Sand

The next question was where to fly it. Wilbur calculated that he

needed a steady wind of at least 15 miles per hour (24 kilometers

per hour) to get the craft airborne. He was also determined to make

his initial flights over sand or water to cushion the impact of a

possible (and extremely likely) crash. At first, he thought of the

Indiana Dunes where Chanute had flown his gliders and he wrote the

U.S. Weather Bureau for the average winds in the Chicago area from

August through September. (This was the off-season for the bicycle

business when the brothers could best afford to take some time off.)

The Bureau replied with a list showing the average wind velocities

in 150 cities throughout the United States.

Safety Net

Safety Net

On 13 May 1900, Wilbur wrote to Octave Chanute at his home in

Chicago for advice, the beginning of a long and fruitful

correspondence. (To read Wilbur's first letter to Chanute, see

below.) Wilbur asked where he might find a sandy, windy location.

Chanute advised Wilbur to consider to consider San Diego, California

and St. James City, Florida. He also said "perhaps even better

locations can be found on the Atlantic coasts of South Carolina or

Georgia." Wilbur checked the material he had been sent by the Weather

Bureau. Sixth on the

list was an out-of-the way place in North Carolina with vast stretches of sand and water,

few trees, and relatively high winds. It was called Kitty Hawk.

Kitty Hawk

It was a tiny village on the North Carolinian barrier islands or

"outerbanks,"

long narrow strips of land just a few miles off

the Atlantic shore. They were entirely made of sand that had

accumulated as a result of the complex interaction between wave

action, sea level, and sediment. In the immediate area around

Kitty Hawk, the wind had whipped the sand into huge dunes, some of

them towering over 300 feet (91 meters). Just south of Kitty Hawk,

there were several especially high dunes known as Kill Devil Hills.

The average wind speeds for September were 16.3 mph (26.2 kph).

On 3 August 1900, Wilbur wrote the Weather Bureau office at Kitty Hawk, inquiring about the area.

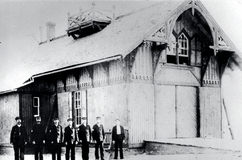

Joseph J. Dosher, the single Weather Bureau employee at Kitty Hawk (also the

chief of the Life Saving Station) said they had a beach a mile wide without trees or other

obstructions. The winds in the autumn blew from the north or northeast.

Boarding was available in the village, but they would have to bring tents

for lodging. Dosher passed the letter to

Captain William Tate, the local notary, county commissioner, former postmaster,

and the only "banker" in Kitty Hawk who had been to high school. Tate sent

Wilbur a warm response.

"I will take pleasure in doing all I can for your convenience & success &

pleasure," wrote Tate, "& I assure you [that] you will find a hospitable

people when you come among us."

Bankers

|

Comparing the rigging of the 1896

Chanute-Herring Glider with the 1900 Wright Glider. Both have

bracing wires along the span (shown in red). However, every bay on

the Chanute is braced across its chord (blue), while on the

Wright, only the middle bay is braced.

To allow the wings to twist, the Wrights developed this unique

"hook-and-eye" hardware to attach the struts to the wings.

A coastal navigation chart from 1900, showing Kitty Hawk. The

location of Bill Tate's house and post office is circled.

In 1899, Kitty Hawk had about 250 residents, most

living on the "bay" side of the island.

Kill Devil Hills, just south of Kitty Hawk.

The Life Saving Station and Telegraph Signal Office

at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina was one of the very few structures on the

"ocean" side of the island. |