|

Up

Up

The

The

Smithsonian

Contract

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

ne

of the many bones of contention between historians who believe the

Wright brothers were the first to make a controlled and sustained

powered flight and those who put forth other candidates is a

contract between the Smithsonian Institution and the Wright Estate.

Dated 23 November 1948, almost a year after Orville Wright's death,

the agreement was the direct result of the

long feud between Orville

Wright and the Smithsonian. The two disagreed whether the Wright

brothers or

Samuel P. Langley, the former Secretary of the Smithsonian,

deserved the credit for having developed the first successful

aircraft. The

resolution of this disagreement defined the meaning of a successful

airplane. ne

of the many bones of contention between historians who believe the

Wright brothers were the first to make a controlled and sustained

powered flight and those who put forth other candidates is a

contract between the Smithsonian Institution and the Wright Estate.

Dated 23 November 1948, almost a year after Orville Wright's death,

the agreement was the direct result of the

long feud between Orville

Wright and the Smithsonian. The two disagreed whether the Wright

brothers or

Samuel P. Langley, the former Secretary of the Smithsonian,

deserved the credit for having developed the first successful

aircraft. The

resolution of this disagreement defined the meaning of a successful

airplane.

Samuel Langley had been an active experimenter

with mechanical flight since the 1880s. In 1896, he flew two large

steam-powered aircraft he called "aerodromes" repeatedly for

sustained flights of up to 4000 feet (1219

meters). The aircraft were unmanned and uncontrolled, but the

flights attracted much attention. Two years later in 1898, the War

Department gave Langley $50,000 to create an aerodrome capable of

carrying a man. Langley attempted to fly his "Aerodrome A"

twice on 7 October 1903 and 8 December 1903 with

Charles Manly as a very brave pilot. On both occasions Aerodrome A

slid into the Potomac River after being catapulted from a houseboat.

These were extremely embarrassing moments for the Smithsonian and

the War Department, both of whom were ridiculed mercilessly in the

press. All this took place just before the Wright brothers succeeded

in flying on 17 December 1903.

In 1906, the Wright brothers were granted a patent for a control

system that could steer an aircraft in three axes – roll, pitch, and

yaw. It was not, as many people believe, a patent on the powered

airplane. The concept of the fixed-wing airplane had first been

proposed in 1799.

Alphonse Penaud created a rubber band-powered model which flew

successfully in 1871, possibly the first sustained powered airplane

flight. But like Langley's later flights, it too was uncontrolled.

The first experimenter to successfully control an aircraft was

Otto Lilienthal, who made glider flights between 1891 and 1896.

However, he controlled his craft by shifting his weight, effecting

roll and pitch only. Full three-axis control wasn't achieved until

1902 when the Wright brothers flew a glider with aerodynamic control

surfaces. This is what they patented. They married their control

system to a powered aircraft in 1903 to make the first controlled

and sustained powered flights.

It was this three-axis aerodynamic control system that other

experimenters copied. In 1909, the Wright brothers launched patent

suits to protect their intellectual property and their most

persistent opponent was Glenn Curtiss. The courts ruled against

Curtiss in 1913 and 1914, but he appealed on the grounds that other

aircraft could have flown before the Wright Flyer. At the same time

Charles Walcott, who had taken over the Smithsonian Institution when

Langley died, was helping the Smith to rebuild its reputation after

the Aerodrome fiasco. The two men realized that flying the Aerodrome

would solve both their problems, and the Smithsonian loaned Curtiss the

remains of Langley's Aerodrome A. He rebuilt the aircraft

making many changes to improve structural strength, lift, power, and

controllability.

On 28 May 1914, Curtiss made a few hop-flights off

the surface of a lake. This ruse had no effect on the patent suit,

but it was balm for the bruised egos at the Smithsonian. Upon

getting the Aerodrome A back from Curtiss, they proudly

displayed the aircraft at the Arts and Industries Building with a plaque that claimed it

was the first airplane "capable" of manned flight.

Orville was livid and

thus began a feud that he eventually won in

the courts of public opinion. He sent the 1903 Wright Flyer –

considered a national treasure by many – to England to underscore

the ridiculous position of the Smithsonian. Even if the Aerodrome

A had been "capable" of flight (and later studies would show

that it wasn't), it simply hadn't flown in its original condition.

To bring the Flyer back, Orville demanded that the Smithsonian

apologize and admit the error of their ways.

This they finally did

in 1942, and in 1943 President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with Orville's

assent, announced the Flyer would be returning to America. Unfortunately there was a world war on at the time and no

one got around to packing up the airplane and sending it back to

America until Orville was deceased.

Harold Miller, the husband of Orville's niece and the executor of

his estate, thought that something should be done to prevent the

Smithsonian from backpedaling. The feud seemed to be over, but it

was still fresh in everyone's memory. A change of Secretaries at the

Smith and it might be back on. So Miller, on behalf of the Wright

Estate, insisted on an agreement with the Smithsonian. The Wright

Flyer would continue to be used as leverage on the side of the

angels. If the Smith ever identified another aircraft as the first

to make a controlled, powered manned flight, the Wright heirs could

reclaim this national treasure.

The full text of this agreement is included at the end of this

web page. It is a challenging piece of legalese, a source of more

obfuscation than clarification for those who don't speak the

language. But if you parse the sentences and paragraphs, the

Smithsonian and the Wright Estate agreed on these points:

- The Estate of Orville Wright agrees to sell the 1903 Wright

Flyer to the United States

(represented by the Smithsonian) for $1.

- In return, the United States guarantees the aircraft to be

displayed prominently in the nation’s capital and to be

identified as the first heavier-than-air flying machine in which

men made a controlled and powered flight.

- The airplane is to be valued at $1 for tax purposes.

- Should the United States not prominently display the

airplane, display it without the agreed-upon identification, or

identify another airplane as being capable of controlled and

powered manned flight before December 17, 1903, the ownership of

the airplane reverts to the Estate.

- Additionally, if the airplane is valued at more than $1 and

the Estate is assessed for taxes, the United States will pay those

taxes. If it does not, the title reverts.

- If the United States forfeits its title to the airplane for

any of these reasons, it has five years to comply with the

agreement to regain title.

This was not a clandestine conspiracy as some have claimed. It

was entered in the public record when the court of Montgomery County,

Ohio probated the Wright estate after Orville's death and it

remained public record from that point on. As far as the Smithsonian

was concerned, these sorts of agreements are common between museums and

donors. The folks who own the Hope Diamond certainly didn't lend it

to the Smithsonian with the understanding it might someday be

hidden away in the basement. It's a safe bet that the donors and the

Smith have an understanding that it will be prominently displayed,

it will be properly identified, and that the valuation of the gem

will not result in unwarranted taxes.

It's also a common policy to keep these agreements from public

eyes to protect the privacy of the donors, although this particular

agreement was always public record.

Still, the Smithsonian did not advertise it – not because of any

conspiracy, but because it was evidence that the Smithsonian had

behaved badly in trying to credit Langley and his Aerodrome A

with honors they did not deserve. But when Senator Lowell Weicker

requested a copy for Whitehead supporter William O'Dwyer, the

Smithsonian provided it. The agreement was showcased in O'Dwyer's

1978 book, History by Contract. There was no need for

O'Dwyer or Weicker to employ the Freedom of Information Act, as has

been erroneously reported. This is still the case – the Smith

released one to us just for the asking. This is in the

interest of the public, the Smithsonian, and the Wright brothers.

Those who take the time to read it fail to find evidence of a

conspiracy to hide the truth. Most of it is mundane. The clause that

seems to give the most offense to those who would challenge the

Wrights' primacy is Paragraph 2(d):

"Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors nor

any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities, administered

for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution

or its successors, shall publish or permit to be displayed a

statement or label in connection with or in respect of any

aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright

Aeroplane of 1903, claiming In effect that such aircraft was

capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled

flight."

It seems ironclad, but it lacks clarity. The word "capable" of

course is a direct poke at the Smith's attempt to promote the

Aerodrome A. But the writer does not define "controlled flight"

as millions of pilots came to understand it – three-axis control.

And there is nothing here that clearly says the aircraft must have

sufficient power to sustain flight. Technically, a glider would

qualify using Wilbur's own argument that soaring machines have a

"gravity engine" for power. There are loopholes here you could fly

an airplane through – a poorly-controlled, underpowered airplane.

Furthermore, when read in context with the remainder of the

agreement, this does not prevent the Smithsonian from investigating

alternate versions of aviation history. It simply says that should

the Smithsonian take the position that someone other than the Wright

brothers made a controlled and powered flight before 17 December

1903, they should be prepared to forfeit the airplane.

It's also worth noting that this agreement was struck in 1948.

For the first half of the twentieth century, the Smithsonian was

free to endorse any inventor or any airplane they deemed first to

fly. There was certainly enough time to investigate other claims as

they came to light. For example, there were 13 years between the

time that Randolf and Phillips published the story of Gustave

Whitehead in the January 1935 edition of Popular Aviation and

the signing of the agreement, during which time the story was

investigated by Harvard University and found wanting.

Furthermore from 1929 on, the Guggenheim Chair (top dog in the

Aviation History section) of the Library of Congress was occupied by

Albert F. Zahm, a man who had been highly critical of the Wright

brothers since he testified against them in the patent suits of

1909-1913. Zahm actively sought information that would negate the

Wright brothers' accomplishments. During the end of his career, he

even offered a reward for photographic evidence that would prove the

Wrights weren't the first to fly. Had he found anything; it

certainly would have been passed to the Smithsonian before the

agreement was signed.

All this nitpicking aside, the agreement is a deterrent. Even if it

were someday proved that some earlier airplane made a sustained and

controlled flight before the Wright Flyer, the Flyer would remain a

national treasure. History has long established that the succession

of Wright experimental aircraft built between 1899 and 1905 gave

birth to aviation. And no one disputes that it was the Wrights who

developed the basic skill set needed to pilot an aircraft with

three-axis controls, and then taught these skills to others. If

other experimenters beat the Wrights to the punch, they did not

effectively communicate their accomplishments. Regardless of who

flew first, every successful aircraft in the air today traces its

lineage back to the 1903 Wright Flyer. That would be difficult for the

Smithsonian to forfeit, as Tom Crouch, Senior Curator of the Smithsonian's

Air & Space Museum, said in press release on 15 March 2013:

"The contract remains in force today, a

healthy reminder of a less than exemplary moment in Smithsonian

history. Over the years individuals who argue for other

claimants to the honor of having made the first flight have

claimed that the contract is secret. It is not. I have sent many

copies upon request. Critics have also charged that no

Smithsonian staff member would ever be willing to entertain such

a possibility and risk losing a national treasure. I can only

hope that, should persuasive evidence for a prior flight be

presented, my colleagues and I would have the courage and the

honesty to admit the new evidence and risk the loss of the

Wright Flyer. "

We hope so, too, and would applaud their grace under immense

pressure.

However, perhaps it's time for a change. Langley-inspired politics are no

longer a threat to the Wright legacy. There has been no credible

challenge to the Wright's title as the first to make a controlled

and sustained powered flight for over a century, and there is none

now despite recent chest thumping about analysis of photos within

old photos. A joint statement from the Smithsonian and the Wright

heirs saying that they will consider amending the agreement should

someone present credible evidence of ante-Wright flight would affirm

public confidence in what most scholars know to be plain,

unvarnished aviation history. It would diffuse one of the most

often-used arguments against the Wrights' historic status and would

send the conspiracy theorists scrambling for another conspiracy.

More Information

|

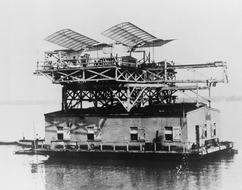

Langley's Aerodrome A

mounted on a catapult atop a houseboat afloat in the Potomac River

near Quantico, VA.

Workmen assemble the Aerodrome A

on its catapult. The wings were considered so fragile, they couldn't

be put in place unless the wind was below 5 mph (8 kph).

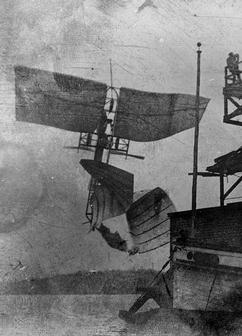

The Aerodrome A drops into

the river just after it was launched on 8 December 1903. The rear

set of wings collapsed immediately after it left the catapult.

The Aerodrome A lies

crumpled on the river. Manly, who was wearing a cork life vest, was

trapped under the wreckage briefly but escaped unharmed.

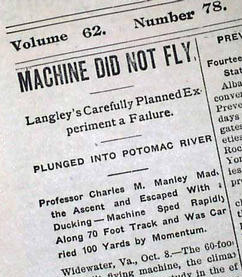

Both of Langley's attempts to fly made the newspapers worldwide.

Glenn Curtiss in the newly rebuilt cockpit of the

Aerodrome A. Albert Zahm

(front left) and Charles Manly (front right) are seated on a

pontoon.

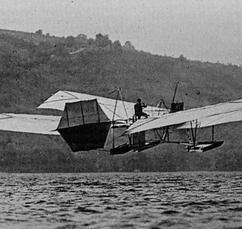

The modified Aerodrome A is

towed onto Lake Keuka near Hammondsport, NY. Read more about the

1914-1915 test flights

HERE.

Among the many modifications made to the

Aerodrome A was the addition

of a Curtiss V-8 engine and a modern propeller. However, it did make

several flights with the original Manly-Balzer engine and Langley

propellers.

Three separate pilots flew the modified

Aerodrome A – Glenn Curtiss,

Elwood Doherty, and Walter Johnson. The best flight was about 20

miles

(32 kilometers) in a straight line, although with the Manly-Balzer

engine the aircraft could only make unsustained hop-flights of

150-200 feet (46-61 meters).

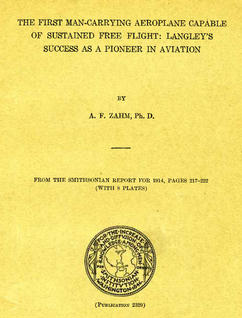

The cover of the 1915 Smithsonian report on Curtiss' test flights of

the Aerodrome A, written by

Alfred Zahm. Zahm mentioned the modifications, but gave the distinct

impression that these were made after the Aerodrome had first been

flown in its original configuration.

Aerodrome A was returned to

its original configuration (without modifications) and installed in

the Smithsonian in 1918. The plaque read: "Original Langley Flying

Machine, 1903. The first man-carrying airplane in the history of the

world capable of sustained free flight..."

Today, Aerodome A is on

display at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum Annex at the Dulles

Airport in Virginia.

|

|

|

|

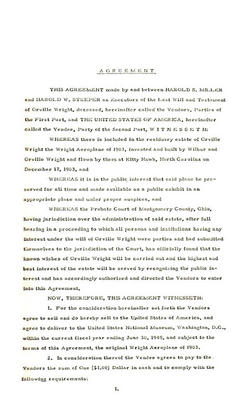

The full text of the contract between the Wright Estate and the

United States of America (as represented by the Smithsonian

Institution):

AGREEMENT

THIS AGREEMENT made by and between

HAROLD S. MILLER and HAROLD W. STEEPER as Executors of the Last Will

and Testament of Orville Wright, deceased, hereinafter called the

Vendors, Parties of the First Part, and THE UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA, hereinafter called the Vendee, Party of the Second Part,

WITNESSETH:

WHEREAS there is included in the

residuary estate of Orville Wright the Wright Aeroplane of 1903,

invented and built by Wilbur and Orville Wright and flown by them at

Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, and

WHEREAS it is in the public interest that said plane be preserved

for all time and made available as a public exhibit in an

appropriate place and under proper auspices, and

WHEREAS the Probate Court of Montgomery

County, Ohio, having jurisdiction over the administration of said

estate, after full hearing in a proceeding to which all persons and

institutions having any interest under the will of Orville Wright

were parties and had submitted themselves to the jurisdiction of the

Court, has officially found that the known wishes of Orville Wright

will be carried out and the highest and best interest of the estate

will be served by recognizing the public interest and has

accordingly authorized and directed the Vendors to enter Into this

Agreement,

NOW, THEREFORE, THIS AGREEMENT

WITNESSETH;

1. For the consideration hereinafter set

forth the Vendors agree to sell and do hereby sell to the United

States of America, and agree to deliver to the United States

National Museum, Washington, D.C., within the current fiscal year

ending June 30, 1949, and subject to the terms of this Agreement,

the original Wright Aeroplane of 1903.

2. In consideration thereof the Vendee agrees to pay to the

Vendors the sum of One ($1.00) Dollar in cash and to comply with the

following requirements:

(a) Said aeroplane is to be displayed

in a public museum exhibit in the Metropolitan Area of the United

States National Capitol only, and except as hereinafter provided in

paragraph (b) to be housed directly facing the main entrance in the

fore part of the North Hall of the Arts and Industries Building of

the United States National Museum. It shall never be removed from

such public exhibition except as may be required temporarily for

maintenance and protection.

(b) If the proper authorities of the

Smithsonian Institution or its successors (acting for the United

Status of America) at any time in the future desire to remove said

aeroplane to any other building in the Metropolitan Area of the

national capital, such removal shall be permitted on the following

conditions:

(1) That the substituted building shall

have equal or better facilities for the protection, maintenance and

exhibition of the aeroplane.

(2) That the Wright Aeroplane Of 1903

be given a place of special honor and not intermingled with other

aeroplanes of later design.

(3) That such building be not a

military museum but be devoted to memorializing the development of

Aviation.

(c) There shall at all times be

prominently displayed with said aeroplane a label in the following

form and language:

“The Original Wright

Brothers' Aeroplane

The World's First Power-Driven Heavier-than-Air Machine

In Which Man made Free, Controlled, and

Sustained Flight

Invented and Built by Wilbur and Orville Wright

Flown by Them At Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

December 17. 1903

By Original Scientific Research the Wright Brothers discovered

the Principles of Human Flight

As Inventors, Builders and Flyers They Further Developed the

Aeroplane

Taught Man to Fly and Opened the Era of Aviation.

Deposited by the Estate of Orville Wright.”

“’The first flight lasted only twelve

seconds, a flight very modest compared with that of birds, but it

was nevertheless the first in the history of the world in which a

machine carrying a man had raised Itself by its own power into the

air in free flight, had sailed forward on a level course without

reduction of speed, and had finally landed without being wrecked.

The second and third flights were a little longer, and the fourth

lasted 59 seconds covering a distance of 852 feet over the ground

against a 20 mile wind.’

Wilbur

And Orville Wright

(From Century Magazine, Vol. 76, September 1908, p. 649)”

(d) Neither the Smithsonian Institution

or its successors nor any museum or other agency, bureau or

facilities, administered for the United States of America by the

Smithsonian Institution or its successors, shall publish or permit

to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in

respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the

Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming In effect that such aircraft was

capable of carrying a. man under its own power in controlled flight.

3. The title and right of possession to be

transferred by the Vendors hereunder shall remain vested in the

United States of America only so long as there shall be no deviation

by the Vendee from the requirements in the foregoing paragraph, and

only so long as neither the Estate of Orville Wright nor any person

having an interest therein is required to pay and does bear without

indemnity an estate or inheritance tax, assessed by the State of

Ohio, the United States or any other taxing authority, based upon a

valuation of property of the Estate which includes said aeroplane

at a value in excess of One ($1.00) Dollar.

4. Upon the failure of the Vendee to remedy any

deviation from the requirements set forth in paragraph 2, within

twelve months after written specification thereof shall have been

given to the Smithsonian Institution on behalf of the United States

or upon (a) the final assessment of any state or federal

inheritance, succession or estate tax whereby the Estate of Orville

Wright or any person or persons having an interest therein shall be

required to pay a higher tax by reason of a valuation of said

aeroplane for tax purposes in excess of One ($1.00) Dollar, and (b)

the omission of the United States or others on behalf of the United

Slates within twelve months of written notice of the final

assessment by the person assessed to provide for the payment thereof

by appropriations or otherwise, title to and right of possession of

said aeroplane shall automatically revert to the Vendors, their

successors and assigns.

5. In the event of a termination of title in the

United States by reason of an omission on the part of the United

States to provide for that In the event of a termination of title in

the United States by reason of an omission on the part of the United

States to provide for the payment of a tax assessment a aforesaid,

the United States shave have the option to repurchase the plane at

any time with five years of the tax payment by reimbursing the

taxpayer in the amount paid with interest thereon at six per cent

from the date of payment. Upon the exercise of such option, this

Agreement, in all of its terms shall automatically again become of

full force and effect.

Witness the due execution thereof here in duplicate this 23rd

day of November, 1948.

(signed)

Harold S. Miller

Harold W. Steeper

Executors of the Estate of Orville Wright, deceased;

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY A. Wetmore

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

|

Page 1 of the original contract.

Page 2.

Page 3.

Page 4.

|