|

Up

Up

Landing

Landing

Without

Crashing

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

he

pioneer aviation era literally flew by, lasting just

a little more than a decade from the first wavering flights at Kitty

Hawk to the beginning of World War I. By this time "second

generation" aircraft had begun to emerge, combining both maneuverability

and stability. This rapid development is all the more remarkable

when you consider that for the first few years, the Wright brothers

were the only successful pioneers. A few visionaries in America and Europe made

brief hops in a handful of airplanes, but nothing approaching the

performance of the Wright Flyer in its final 1905 form. This despite the fact that

these builders had access to the Wrights' published patents. It

wasn't until the Wrights began demonstrating their airplane in 1908

that the rest of the world fully understood the necessity of

three-axis control and how to use it. he

pioneer aviation era literally flew by, lasting just

a little more than a decade from the first wavering flights at Kitty

Hawk to the beginning of World War I. By this time "second

generation" aircraft had begun to emerge, combining both maneuverability

and stability. This rapid development is all the more remarkable

when you consider that for the first few years, the Wright brothers

were the only successful pioneers. A few visionaries in America and Europe made

brief hops in a handful of airplanes, but nothing approaching the

performance of the Wright Flyer in its final 1905 form. This despite the fact that

these builders had access to the Wrights' published patents. It

wasn't until the Wrights began demonstrating their airplane in 1908

that the rest of the world fully understood the necessity of

three-axis control and how to use it.

From that moment,

aviation accelerated at an unprecedented rate – and for good reason.

Across the globe, politicians were struggling mightily to maintain

the "balance of power." Diplomacy had become a tangled web of

treaties promising mutual aid in the event of attack. Germany was

locked in an arms race with France and England. World war was

imminent and the airplane looked to be a versatile and deadly

weapon.

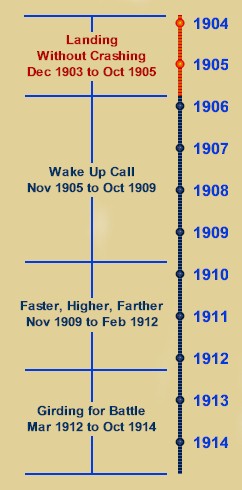

- Landing Without Crashing, 1903 to 1905

–

The Wright Brothers develop their temperamental Kitty Hawk Flyer into

a practical flying machine.

- Wake Up Call, 1905 to 1909

–

The Wright brothers accomplishments alert aeronautical

scientists and engineers in America and Europe to the

possibilities of fixed wing aviation.

-

Faster, Higher, Farther, 1909 to 1912

– Pilots and engineers

begin to explore the capabilities and push the possibilities of

aircraft.

- Girding for Battle, 1912 to 1914

– As the First World War

approaches, nations develop the airplane into a weapon.

|

|

Time

|

Event

|

|

1903 |

December

— On the train ride from

Kitty Hawk to Dayton, the Wright brothers decide to

continue their aeronautical work until they have developed

their Flyer into a "practical" flying machine. Wilbur later

defines a practical flying machine as one that can take off

in a wide range of weather conditions, navigate to a

predetermined location, and "land without crashing."

|

|

Although the Wrights made four successful flights on

December 17, 1903, the same cannot be said of their

landings. None of them were planned and the fourth and last

landing damaged the elevator.

|

|

1904 |

January 5

— Hoping to quash all the

fantastic rumors about their airplane, the Wrights

issue a statement to the Associated Press describing their

first powered flights at Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903.

January 22 —

The Wrights engage attorney Harry A. Toulmin

of Springfield, Ohio to handle their patent applications.

March — Ernest

Archdeacon, France puts up a purse of 25,000 francs for the first officially

recorded circular flight of one kilometer, called the Grand Prix d’Aviation,

to be awarded by the Aéro-Club de France. French

oil magnate Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe matches Archdeacon, raising the

prize to 50,000 francs, or about $10,000.

March 22-24

—

Harry A. Toulmin

applies for the French and German patents on the Wright

airplane.

March-May

— The Wrights build a second

airplane, the Flyer II. It is a copy of their first

Flyer, but it has a more powerful motor (18 hp).

Spring Alberto Santos-Dumont, France, a

pilot famous for his pioneering work in dirigibles, begins to experiment with gliders.

April 1-15 —

Ernest Archdeacon tests a "type du Wright" glider

near Berck-sur-Mer, France, piloted by Ferdinand Ferber

and Gabriel Voison. Although the glider is based on

the 1902 Wright design, the wings are shorter, the camber

deeper, and there is no roll control. Archdeacon considers

its performance unsatisfactory.

May — Robert

Esnault-Pelterie, France, tests a type du Wright

glider, but he has trouble with the wing warping and

determines to improve it.

May 23-26 — The Wrights attempt to fly at Huffman

Prairie, near Dayton, Ohio before the press on two occasions with their new machine, the Flyer II.

But even with a more powerful motor, it can only manage brief hops. The

press is kind, but unimpressed.

July 1 — The first of the Wright’s

patents (French) is granted.

August 13 — Wilbur makes a flight of

1340 feet (408 meters) in the Flyer II, beating his performance in

Kitty Hawk for the first time. But the brothers are still have trouble getting into the air and staying there.

September 7 — The Wrights develop a catapult

launching system to get their aircraft up to flying speed. It works well, and they begin

to make progress again.

September 20 — Wilbur Wright flies the

first complete circle in an airplane. The flight is witnessed by Amos Root,

inventor of the modern bee hive and publisher of Gleanings in Bee Culture.

October —

Robert Esnault-Pelterie tests a rebuilt version of his

glider with primitive elevons mounted forward of the wings.

October —

Ferdinand Ferber rebuilds his glider with an elevator in

front and the fixed horizontal tailplane in back. He also

mounted to triangular wingtip rudders. While testing this

glider, he takes his mechanic, Marius Burdin, aloft for a

short flight, making him the first passenger in a

heavier-than-air machine.

October —

The Aéro-Club de France adds to their list of

prizes to encourage the development of aviation in France.

The Coupe Ernest Archdeacon consists of a trophy and

1500 francs. The trophy goes to the first aviator to fly 25

meters (82 feet) and the cash to the first to fly 100 meters

(328 feet). The Prix pour record de distance will

award a silver medal and 100 francs to the first 10 pilots

to fly 60 meters (197 feet) and 1500 francs for the first to

fly 100 meters. As aviation progresses, the Aero-Club

will offer additional prizes for flights of 150, 300, and

500 meters (492, 984, and 1640 feet).

October 15 —

Lt. Col. John E. Capper of the British Army visits to

Wrights in Dayton to obtain information on their airplane

and express an interest in buying it.

November 9 —

Wilbur flies for 5 minutes and 4 seconds, traveling

2-3/4 miles (4.4 kilometers) and completing 4 circles around

Huffman Prairie. It is the best flight of the season.

|

The fantastically inaccurate story that was fabricated for

the Virginia Pilot

newspaper was picked up by many other papers nationwide.

This appeared in the

Chicago Tribune.

Ernest Archdeacon.

Santos Dumont flying his

No. 6 dirigible in Paris, France.

Esnault-Pelterie represented his first glider as an exact

copy of the Wrights' 1902 design, but like so many of his

French buddies, did not understand the purpose or the

mechanics of wing warping.

The soft soil at the prairie was a wise choice. A number

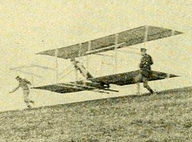

of the Wrights' flights ended like this one on 16

August 1904.

The pages from Wilbur's notebook that record the first circular flight.

Ferber's 1904 glider design with an elevator in front and a

horizontal tail in back would have enormous influence of

later French designs.

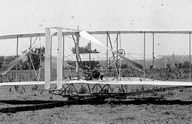

Wilbur keeps the Flyer II

aloft for just over 5 minutes on 9 November 1904.

|

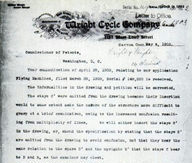

Until they engaged Harry Toulmin in 1904, the Wrights had

tried unsuccessfully to file their own patent, as this

letter indicates.

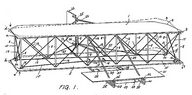

The patent drawings that Toulmin prepared show the 1902

glider, not the 1903 Flyer. Toulmin focused the patent

application on the Wrights' single most important

accomplishment – their control system.

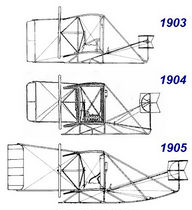

The Wrights realized that four flights in their first Flyer

didn't provide enough experience, so the Flyer II was a copy

of the first to allow them to thoroughly test the design.

Voisin flies Archdeacon's glider at the sand dunes on the

French side of the English Channel.

Huffman Prairie had been a failed peat bog. The "frost

heaves" every winter fluffed up the soil, making it very

soft.

The Wright catapult consisted of a high derrick (right) that

dropped a heavy weight, pulling the Flyer along the launch

track.

Having tried and discarded wing-warping, Esnault-Pelterie

reworked his glider with elevons or "little wings," as he

called them. These were the forerunners of ailerons.

Lt. Col. John Capper (left), later Sir John Capper, was one

of the driving forces behind Britain's pioneer aviation

programs.

|

|

1905 |

January 1 — After

trying and failing to interest Scientific American,

Amos Root publishes an eyewitness account of the

Wrights' 20 September 1904 flight (the first circle ever

flown) in his own publication, Gleanings in Bee Culture.

January 3 —

Wilbur Wright meets with Ohio Congressman Robert M.

Nevin to discuss selling their airplane to the United

States military. Nevin suggests writing a letter which he

will hand-carry to President Taft.

January 18 —

Wilbur writes the letter requested by Nevin.

Owing to a miscommunication, the letter is forwarded to the

US Department of War. Nevin has no chance to present

the Wright's proposal in person to the President.

January 26 —

Nevin's office forwards a letter from Maj. General

George L. Gillespie of the US Board of Ordinance and

Fortification to the Wrights declining their offer, saying

that "their machine had not yet been brought to a state of

practical operation."

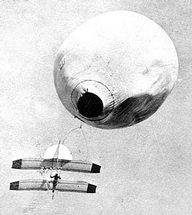

March-July — John

J. Mongomery lifts a tandem-wing glider and pilot

Daniel Maloney aloft in a balloon over California to

altitudes of up to 4000 feet (1219 meters), then releases

them to glide down.

March 1 — The

Wrights offer their airplane to the British War

Office.

March 26 — Ernest

Archdeacon tests a second glider with a fixed horizontal

tailplane similar to Ferber's 1904 design.

May 13 — The

British War Office requests that their military attaché

in Washington be allowed to observe the Wright airplane in

flight.

May-June — The

Wrights build a third Flyer, scavenging the drive

train and hardware from the second one. The new Flyer III

incorporates many improvements.

Summer — Samuel F.

Cody, an American ex-patriot building "war kites" for

the British, flies a "kite glider" at the Crystal Palace. He

kites the glider and the pilot aloft, then glides down.

June 8 and 18 —

Gabriel Voison builds and flies a "float glider" for

Ernest Archdeacon, towing it behind a motorboat on the

Seine river. The design marries the Wright glider biplane

wings and forward elevator with a box-kite tail.

June 23 — The

Wrights begin to test the Flyer III. It still

presents many control issues, particularly in pitch.

July 14 — Orville crashes

the Flyer III. It is a serious accident and plainly due to lack of

control. The Wrights decide to rebuild the Flyer again, extending the

elevator and the rudder further out from the wings to make them more

effective.

July 18 — After

the impressive tow-flights of the Voison-Archdeacon glider, Louis Blériot

engages Gabriel Voison to build

and test another float-glider. Like the

first, they test it on the Seine River, towing it behind a motorboat. Voison quickly loses control and the glider crashes.

July 25 —

Carl Dienstbach, American

correspondent of Illustrierte Aeronautische Mitteilungen

(Illustrated Aeronautical Communications) in Germany,

visits the Wrights in Dayton. He subsequently becomes a

supporter and an important source of information about the

Wrights for the Europeans.

August 24 —

The Wrights begin to test-fly the rebuilt Flyer

III. In less than a week, they are flying multiple

circuits around the Prairie and landing under control

without damaging the Flyer.

September 26 —

After flying for 18 minutes, Wilbur runs the Flyer

III out of fuel and coasts to a gentle landing. This is

the first in a series of extended flights.

October 4 and 5 — The Wrights fly

publically before many witnesses, including journalists. Wilbur makes

the best public flight on October 5, remaining in the air for 39 minutes,

traveling 24 miles (39 kilometers), and landing only when the gas tank runs dry.

October 9 — The

Wrights again offer their airplane to the US War

Department. They also write to Ferdinand Ferber,

describing the success of their 1905 flying season and

offering to sell the airplane to the French.

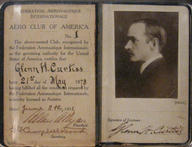

October 12-14 — At a

meeting in Paris, the Aero Clubs of eight countries –

France, England, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Switzerland,

Italy, and the United States – come together to form the

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale "...to advance

the science and sport of aeronautics." It becomes the

governing body of aviation through the pioneer era.

October 16 — The War Department

asks to see detailed plans of the Wright airplane to determine its

practicality. The Wrights decline.

|

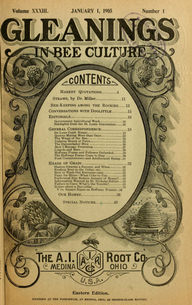

The 1 January 1905 of

Gleanings in Bee Culture carried a story describing

the Wrights' 20 September 1904 flight.

On 18 July 1905, the Montgomery glider was damaged on its

ascent, it failed on the descent and Maloney was killed.

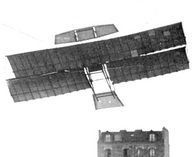

Archdeacon's second glider was never flown by a pilot. It was

towed aloft unmanned and crashed a few moments later

Despite its improvements, the first version of the 1905

Wright Flyer III was still "close coupled" as the previous

Flyers had been. The elevator and rudder were too close to

the wings, creating control problems.

The camber on the Voison-Bleriot float glider was much

deeper than the Voison-Archdeacon machine, making it much

harder to control.

7 September 1905 – After a few mishaps as the Wrights get

used to their new controls, they begin to make uneventful

flights – and safe landings.

4 October 1905 – The Wrights fly before the media for the

first time since May 1904. |

A campaign button for Congressman Robert Nevin.

The United States War Department, Board of Ordinance.

rejected the Wright aircraft because it must first be

brought to a "stage of practical operation." This left

future historians to wonder if the War Department ever read

the Wright proposal since the brothers had clearly stated

they had produced an aircraft of "practical use."

The Cody kite-glider was kited to altitudes of up to 350

feet (107 meters) and soared as far as 740 feet (226 meters) horizontally.

The 1905 Voison-Archdeacon biplane glider, with its forward

elevator and box-kite tail, became a standard configuration

for many European aircraft.

After Orville's crash of 14 July 1905, the Wrights rebuilt

the Flyer III, extending the rudder and elevator out from

the wings. This increased control effectiveness and allowed

the pilot more time for attitude adjustments and

corrections.

29 September 1905 – After gaining more experience, the

Wrights found they could keep the Flyer aloft till it ran

out of gas.

A close-up of Orville Wright flying on 4 October 1905.

The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale disseminated

information about aviation, kept official records, and set

standards, such as the requirements for a pilot's license. |

|

|

|

|