|

Up

Up

Charles Flint

Charles Flint

Remembers

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

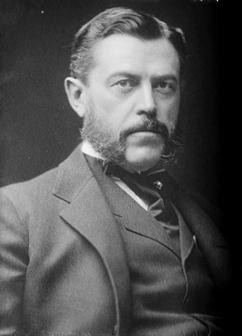

[Ed. – Charles

Ranlett Flint was among the biggest movers and shakers of the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was born in Maine in

1850, but moved to New York City and attended the Polytechnic

Institute of Brooklyn, graduating when he was just 18 years old. He

was a partner in a shipping firm by the time he was 21, through

which he made and cultivated world-wide contacts. His business deals

were the stuff of legends; Flint once sold an entire navy to Brazil.

Flint is best remembered as the "father of the trust." He

arranged mergers between companies with similar products or

services, reasoning that a larger, more diversified company would be

healthier than a smaller, specialized business and better able to

weather economic difficulties. In 1892, he created U.S. Rubber from

several smaller companies. In 1899, he formed a candy trust,

American Chicle, and a textile trust, American Woolen. His crowning

achievement was the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR),

which he built from three companies -- the International Time

Recording Company of Endicott, N.Y.; the Computing Scale Company of

America of Dayton, Ohio; and the Tabulating Machine Company of

Washington, DC. Each was in possession of advanced technology (for

the time) which, when brought together, spurred more advances and

better products. CTR quickly came to dominate its industry and in

1924 changed its name to International Business Machines --

IBM. Flint remained on the IBM board until he retired at the age of

81.

One of Flint's most famous deals involved the airplane. In

fact, some historians suggest that if Flint had not gotten

involved with the Wright brothers and helped them sell their

airplane, the brothers might have passed into obscurity, their

contribution to aviation half-remembered as an idea before its time.

Nonetheless, he jumped in with both feet and introduced the Wrights'

and their airplane to the world. It was a cordial but not an easy business relationship.

Nor was it especially profitable. But Flint was the midwife who

delivered the infant airplane industry and his efforts had

far-reaching effects, beyond his or the Wrights' expectations.

In this extract from his rambling memoirs, Flint remembers the

Wright Brothers and their "aeroplane," and marvels that such a good idea with so much

potential was such a hard sell.]

|

Charles R. Flint

was one of the most powerful men in the world when

he first learned of the Wrights in 1906.

In 1911, Flint founded the high-tech trust that became IBM.

|

|

The aeroplane was

the creation of Wilbur and Orville Wright who, in 1905, were the

first to climb into the skies in a "heavier than air" machine. The

Europeans had talked about what they were doing, and world-wide

publications announced what they expected to do. In 1908 a banquet

was given in Paris to celebrate the success of the Wrights who by

that time had excited considerable jealousy. A speaker, following

Wilbur Wright, known as the man of silence, who had regretted that

he was not an after-dinner orator, remarked that "among the

feathered tribe the best talker and the worst flyer is the parrot."

In the case of

claims for discoveries or inventions, serious questions generally

arise as to rights of priority. For this reason the courts usually

refuse to grant injunctions until patents are adjudicated valid, but

in this case the Wrights were flying while the rest of the would-be

"heavier than air" machine navigators were trying to get off the

ground; so the court naturally made an exception and granted the

Wrights an injunction before adjudication.

The Wrights were

men of high principles and they were public spirited. When a partner

of P. T. Barnum and I elaborated a plan to make a profit of several

hundred thousand dollars by charging admission to see the Wright's

wonder of the air and age, they refused the profit and the public

were admitted free.

England was the

first to seek information about the Wright aeroplane, and as early

as 1904 Colonel Capper, head of the Royal Aircraft Factory, visited

Dayton; but the Wrights were patriotic, and before they would sell

the aeroplane to any other nation they wrote to Washington offering

to turn it over to our government. The reply which they received was

a "snippy" one, and quite in line with the policy which caused

Hotchkiss to go to Paris to exploit his machine gun and which

resulted in our failure to adopt, adapt. exploit, and control the

American submarine inventions of Bushnell, Holland, and Lake. It is

a lamentable fact that most of our soldiers killed in Europe during

the World War were killed by American inventions.

I first took an

intense interest in the Wright aeroplane when our Mr. Ulysses D.

Eddy visited them on Thanksgiving Day, 1906, at their home in

Dayton.

After the United

States Government failed to take advantage of the Wright discovery,

they asked me to offer their aeroplane to England.

In a speech made

in London, Cobb once said "Blood is thicker than water," but owing

to a patronizing speech made by the speaker who preceded him, he

added. "Thank God for the 3,000 miles of water" and abandoned the

speech he had prepared.

The Wrights,

however, without any reservations whatsoever, gave England the

opportunity to be the first to establish a navy of the air. I opened

negotiations with Lord Haldane, the Minister of War, through Lady

Jane Taylor, as I was satisfied that he would give her an immediate

audience. I cabled to her offering for $500,000 ten aeroplanes that

would each fly fifty miles. Haldane replied that a fifty-mile flight

was too short, so I offered him twenty aeroplanes that would each

fly 200 miles for $1,000,000. In reply Haldane told Lady Jane,

"That's Yankee tall talk!" I then offered to exhibit the Wright

aeroplane to Ambassador Bryce, at a club of which I was a member,

about an hour's ride from Washington. I also offered to pay the

costs of demonstration in England and to make a deposit in any bank

in London His Lordship might name to be forfeited in case we did not

make good. His Lordship then suggested to Lady Jane that we send

over plans and specifications. For over two years the British

government had been trying to get information about the Wright

aeroplane; and I sent in cipher an appropriate negative

characterized more by force than by elegance. Soon after I received

the following letter from my Scotch friend Lady Jane:

"You will be

amused that I have been interviewed by order of the Post Office

officially to find out whose code I am using, what the meaning of

certain words is, and in fact to give the show away. The official

sent left me much discomforted by the impracticability of my replies

and fully persuaded of the truth of the Scotch saying, 'Ye can sit

on a rose, ye can sit on a shamrock, but ye canna sit on a thistle!'

"

The Germans were

quicker than any others to recognize the great possibilities of the

Wright aeroplane. It was exhibited by Orville Wright in a park at

Berlin where there were thousands of people to witness the flight.

When the aeroplane was taken across the field there walked in line

behind it the Chief of Staff General Count Moltke, Orville and Miss

Wright, Mrs. Flint, and myself.

After the Berlin

flight, the newspapers stated that the Emperor had extended his hand

to Orville Wright and congratulated him on his achievement. It was

said that the Emperor's words were: "Mr. Wright, you have

revolutionized modern warfare."

I question whether

this statement would have been made by the Emperor under conditions

where it could have been taken seriously. Such a remark might have

been made to disarm suspicion regarding Germany's big aeroplane

preparations. In fact the Germans were generally very diplomatic in

regard to war preparations. They gave out sufficient information to

maintain their prestige in affairs of war in order that German

officers might be the military instructors of the world—even the

Colombian soldiers at Bogota were taught the goose-step march; and

in order to maintain their huge munition plants they encouraged

orders from foreign nations. I was impressed by their prestige when

Major H. R. Lemly, acting with my firm, went to China and other

countries to sell woven military equipment. The fact that the United

States had used it exclusively for five years had little influence;

but when it was stated that the German government was considering

its adoption, government officials became intensely interested.

Not long after the

exhibition of the Wright aeroplane, the Emperor invited to a dinner

twenty prominent men, the majority of whom were interested in the

German dirigible enterprise, and told them that something ought to

be done in Germany to develop the aeroplane. After coffee His

Majesty retired, saying the German equivalent of "It's up to you."

The imperial guests went down into their pockets, including Isador

Loewe who contributed $40,000, and Rathenau who contributed a

smaller sum. In 1908 we sold the Wright invention to a German

company, and in 1909 the Emperor visited the Wright aeroplane

factory in Berlin and inspected the machines.

Some years

earlier, the Krupps had opened negotiations with us for the Lake

submarine inventions. As an evidence of German prestige in affairs

of war, Florio of Naples, hearing of our negotiations, paid our

agent $40,000 in order to secure for Italy a six-month's option on

what we were selling to the Krupps. But after the Germans had

thoroughly satisfied their thirst for knowledge regarding Lake's

inventions, by a careful examination of our plans and

specifications, they omitted the formality of signing on the dotted

line. Florio, inferring from this that the inventions were of no

value, bid good-bye to his $40,000.

We offered the

Wright aeroplane to every minister of war in the world, and wondered

why our offers were unanimously treated with indifference. The

explanation was simply that the Germans did not openly favor

extensive use of the aeroplane for military purposes.

Their apparent

indifference to aerial weapons represented only one phase of a well

calculated plan. The Germans were perfectly willing to furnish the

world with ordinary munitions; but they regarded such munitions as

of secondary importance in comparison with their super-war

armaments, super-aeroplanes, super-submarines, super-cannon—the

cannon which destroyed the Liege forts—the cannon that fired on

Paris at a distance of seventy miles. They realized that world

preparedness was inevitable, but they were confident that the

preparedness of other nations must prove inferior to theirs. While

they amiably forged thunderbolts for foreign purchasers, they

secretly did some super-forging on their own account.

When I visited

Essen, four years before the World War, I was cordially received. I

was shown hospitals and the comfortable homes of their laborers. I

was given a seat at the head of a bountiful board where I tasted

many kinds of their vintage wines, and was escorted by one of

Krupp's directors to Dusseldorf; but this truly Teutonic hospitality

hung like a thick curtain between me and the war preparations that I

would have liked to see. At the Koerting factory in Hanover I

observed that the most advanced submarine and torpedo boat engines

were boarded up so they could not be examined.

In France we

formed a company for the exploitation of the Wright inventions.

Wilbur Wright sailed for France in May, 1908, and his first flight

was made at Le Mains on August 8th, of the same year. The French did

not make much progress in their experimenting with heavier than air

machines until after the Wright flights at Le Mains, when they built

aeroplanes based on Wright inventions, which they called "Wright

machines." Contrary to general opinion, theirs was not an

independent parallel development.

Rear Admiral

Bronson. Mrs. Flint and I witnessed the Orville Wright-Selfridge

flight at Fort Myer, and saw the aeroplane fall. I rushed to the

plane with Mr. Charles-White of Baltimore who was noted for his

powers of observation.

''Lieutenant Selfridge." he said, "will probably die— he does not move his

fingers—but Orville does, and will probably survive."

Selfridge died

that evening, the first man to be killed in a power airship.

Mrs. Flint then

and there made me promise never to go up in an aeroplane, and I have

been as faithful as Irvin Cobb was when leaving the German army for

tide water. The colonel made him give his word of honor not to leave

the squad. Cobb knew enough German to understand the colonel's order

to the captain: "If that man Cobb starts to leave the squad, shoot

him at once!"

Cobb told me

later; "I never kept my word of honor so easily."

In declining

requests to go up, I often referred to a precedent established by

the King of Spain. When we invited His Majesty to ascend at Pau, he

replied, "I have promised the Queen not to go."

The Wrights

invited me to be their guest when Lord Northcliffe visited Dayton to

present Orville Wright with the Albert Medal. After lunch at the

Wright home, where I sat at Orville's left, we adjourned to an

auditorium where there were two thousand people. Governor Cox made a

speech the style of which was somewhat redolent of the stump. After

which Lord Northcliffe stepped forward and in a low but impressive

voice said, "Let us rise and stand in contemplation of the memory of

Wilbur Wright." He then and there won the heartfelt esteem of that

audience and talked to them in a conversational way that recalled

the manner of American Commonwealth

Bryce Northcliffe

requested me to ask in his presence whether the Wrights were being

taken care of by the business men of Dayton who were morally

indebted to them as the founders of their aeroplane prosperity, as

he desired that a financial understanding in the Wrights' favor

should be made clear in his presence.

When on the train

homeward bound, I invited Lord Northcliffe to dine at the Dower

House, formerly occupied by the Lords Baltimore, to meet Justice

McReynolds of the United Slates Supreme Court, Patrick Francis

Murphy, Irvin S. Cobb, Major A. E. W. Mason, Robert H. Davis, and

Captain, now Rear Admiral, Sir Guy Gaunt. Northcliffe's adaptability

was shown by his reply: "I must leave immediately for London, but

give me a rain check."

Whether that was

American slang or whether he had in mind a "wet party" I know not;

but the Dower House was just beyond the prohibition boundary of the

District of Columbia.

I had and have

most pleasant relations with the Wrights. Mrs. Flint and I were of

some service when Orville was injured in the fatal flight with

Selfridge; but the Wrights and I did not always agree. Our

discussions were always frank and both parties evinced a desire to

arrive at wise conclusions, but the Wright brothers retained the

power to decide on business policies. I told them that my experience

had satisfied me that patents in themselves as a rule could not be

relied upon; that there was not one patent in ten thousand which

proved to be a basic or master patent; that success in the

exploitation of inventions depended principally on preempting and

extending the commercial field; that patent litigation was

expensive, in the end generally unsatisfactory, and that it was not

popular, as aggressive patent litigation interfered with the natural

evolution of the art.

The Wrights were

not lucky accidental discoverers: they were patient, intelligent,

industrious investigators. At the outset they made use of existing

scientific data but after their Kitty Hawk and Dayton experiments

they decided that they would have to rely on their own

investigations. They did not attempt to keep their work secret and

sent their tables to Chanute, desiring to assist other

investigators. But if our government had had the wisdom to secure

the Wright aeroplane, Wright secrets would then have become state

secrets.

The Wrights

realized substantial sums from their inventions, but these were

insignificant when compared with their scientific and practical

accomplishment. |

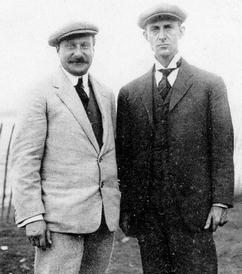

Hart O. Berg (left) was Charles Flint's agent in Europe. He was a

well-connected and well-respected deal-maker, a recipient of the French

Legion of Honor (Ordre national de

la Légion d'honneur). He worked closely with Wilbur

Wright (right) as Wilbur toured Europe making demonstration flights

in 1908 and 1909.

Edith poses with the dog "Flyer." Flyer was a stray that Wilbur

adopted when he was rebuilding his airplane during the summer of

1908. Flyer toured Europe with the Wrights and the Bergs, then Hart

O. Berg and his wife took the dog when the Wrights returned to

America.

Wilbur Wright in the cockpit with King Alphonso XIII (Spain). Hart

O. Berg looks on. According to Orville Wright, European royalty and

the rich were "thick as thieves" at these flying demonstrations.

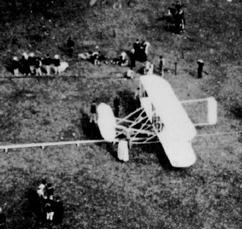

While in Centocelle, Italy, Hart O. Berg snapped this photo of the

Flyer from a tethered balloon.

Hart O. Berg and Charles Flint continued to manage the Wright

interests in Europe for many years. The photo shows Berg (right) with Orville

(left) when Orville came to Germany in late 1909.

Kaiser Wilhelm II (Germany) visits Orville Wright at Tempelhof Field

in Berlin, Germany.

Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm

(Germany) also came to watch the flights. For its percieved

aloofness, Germany was vitally interested in aviation.

Charles Flint himself occasionally traveled to watch the Wrights fly

and to be at hand for negotiations. He and his wife are somewhere in

this crowd trailing the Wright Flyer as it is towed onto the

Tempelhof flying field in Germany.

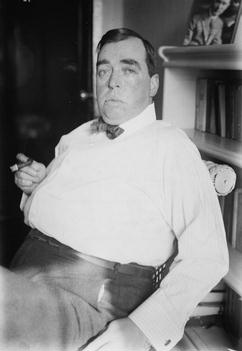

Irvin S. Cobb, whom Charles Flint was so fond of quoting, was a

widely-read journalist and humorist, and a good friend of the

Flints. It's probably a safe bet that Cobb was a great deal funnier

when telling his own jokes than he might seem when Flint re-tells

them.

British newspaper magnate Alfred Harnsworth (Lord Northcliffe) waves

at Wilbur as he passes overhead in Pau, France. Northcliffe was a

passionate supporter of new technologies, including automobiles and

airplanes. He wrote several books on "motor sports."

|